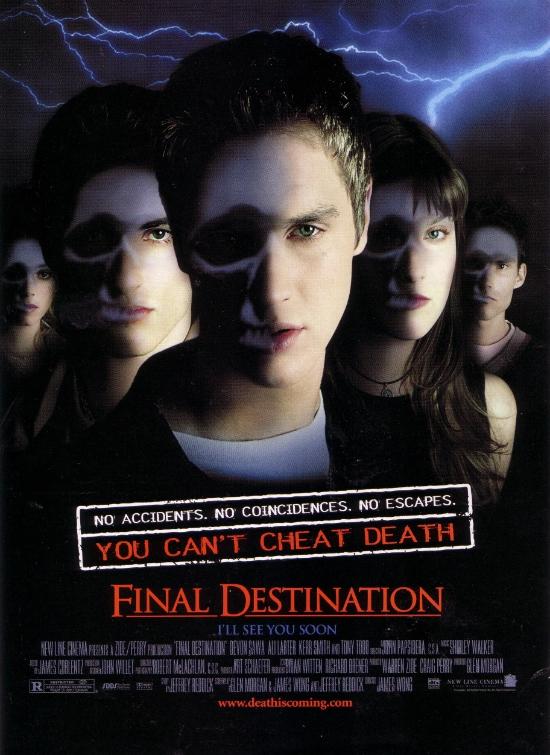

The ultimate “you can run but you can’t hide” experience.

Death, it turns out, is a breeze. Not a violent gust, nor a howling storm – just that soft, curious drift of air, moving with the kind of quiet purpose that makes curtains twitch or a mobile spin with no visible cause. In Final Destination, that gentle ripple is the calling card of something vast and unseen: not a ghost, not a monster, but Death itself, quietly double-checking its appointment book.

The film doesn’t waste much time in getting to the good stuff. One moment, Alex Browning (Devon Sawa) is packing for a class trip to Paris, all teen nerves and long-haul dread; the next, he’s yanked into a vivid, fiery premonition of Flight 180’s catastrophic end. It’s not just a nightmare – it’s a glimpse into a future that is meant to happen. When his panicked reaction results in him and a handful of classmates being thrown off the plane, and the real Flight 180 promptly explodes in mid-air, they’re branded survivors. But the relief doesn’t last. Whatever was supposed to happen that day hasn’t been cancelled – it’s been rescheduled.

This is where Final Destination sets itself apart. It’s not just a film about escaping a horrible death, but also about understanding its method. Death, in this world, is not random. It has order. It has intent. And once you’ve slipped through its fingers, it starts tidying up the mess. The result is a film that plays like a supernatural conspiracy thriller laced with teenage angst.

Devon Sawa, perpetually wide-eyed and sweat-drenched, gives the concept just enough grounded desperation to sell the absurdity. He’s not a final boy in the making – he’s a reluctant prophet who’s read the wrong sacred text: an airline seat pocket safety card. The rest of the cast orbit him like genre archetypes given just enough human texture to make their deaths register. Ali Larter’s Clear Rivers – a name that sounds like a health retreat but thankfully doesn’t act like one – brings oddball gravitas and an energy that feels just adjacent to The X-Files, which makes sense given the film’s origin.

Final Destination was originally cooked up as a spec script for The X-Files, which explains its mood: a bit colder, more fatalistic, more willing to linger on the procedural side of the supernatural. It’s what gives the film its oddly mature streak. Where other horror flicks feel like high school extended, this one feels like graduation day gone awry – the future suddenly stripped of promise and replaced with obligation. Death as admin.

James Wong’s direction is crisp without being flashy, letting the accidents unfold with cruel precision rather than bombast. He’s less interested in repeated jump scares than he is in weaponizing a kind of domestic dread – what if you died in a freak accident? The kills aren’t just gore moments, they’re meticulously prepared dread delivered in unpredictable fashion. Sometimes you get to watch them build, relishing the inevitability; sometimes they arrive suddenly, while the film’s been lulling you into a sense of temporary safety. What’s most impressive, looking back, is how the film seeds its rules and dares you to pick them apart. It invites a conversation about fate, choice, and whether sentient destiny could pass a health and safety inspection. By turning mortality into a logic puzzle, it gave the horror genre a new game to play. Not just who dies, but how – and can it be stopped? This is horror for the overthinker, the anxious, the terminally jinxed.

It’s telling that the franchise never bettered this first outing, even as the sequels embraced gory spectacle with ever more creative carnage. Final Destination remains the purest expression of the concept: death as inevitability, but not inertia. It’s a film about fighting the current even when you know where the river ends. Not because you think you can win, but because not fighting feels like letting it win.

The idea of Death as a conscious, corrective force isn’t just clever – it’s chillingly relatable. Anyone who’s ever narrowly dodged a car or watched a ladder slip with a beat’s grace knows that lurch of borrowed time. The film didn’t just externalise that dread – it gave it a personality. Not a grim reaper, not a shadowy figure, but a presence: methodical, observant, a stickler for detail. Death here is less a villain and more a civil servant of the afterlife, come to straighten up the paperwork.

And that, more than the gore, is what gives Final Destination its enduring edge. It made death impersonal, inevitable, and weirdly interactive. You don’t scream because something jumps out – you scream because you see the dominoes start to fall and can’t do a damn thing about it.