The film that lit the fuse on a franchise that would refuse to self-destruct.

INT: NOC VAULT, CIA HEADQUARTERS, LANGLEY. An impossibly young Ethan Hunt descends fresh-face-first into cinematic legend, dangling from a wire in a tense dead silence. It’s not the first scene, but it might well be the defining moment – the birth of the modern Mission: Impossible – mid-air, meticulous, and madly committed. De Palma’s 1996 reinvention of the classic Cold War spy series isn’t content to just channel the spirit of the original – it straps it to a train, rams it into a tunnel, and launches it at the audience with a subtlety that foreshadows Tom Cruise’s post-mid-life adrenaline addiction.

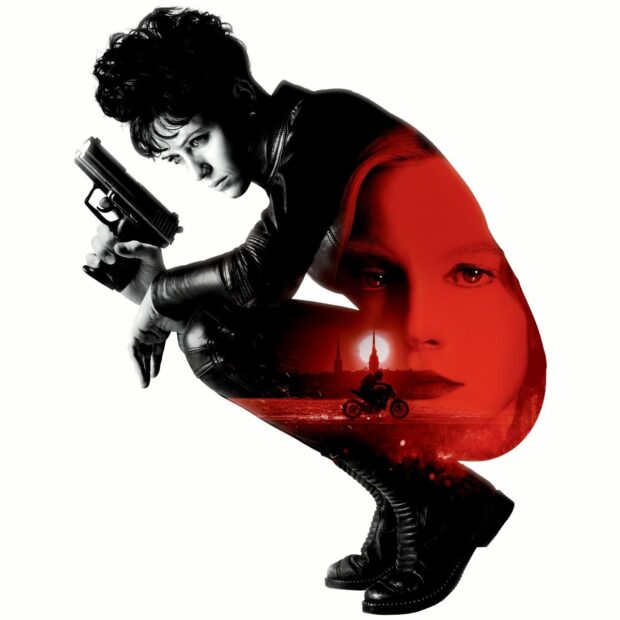

When a covert mission in Prague ends in disaster, IMF operative Ethan Hunt (Tom Cruise) finds himself cut off, disavowed, and suspected of betraying the very organisation he serves. To clear his name and uncover the truth, he must outwit his own agency while navigating a shadowy world of double agents, encrypted files, and shifting loyalties. Enlisting disavowed tech genius Luther Stickell (Ving Rhames), slippery pilot Krieger (Jean Reno), and reuniting with Claire Phelps (Emmanuelle Béart) – the widow of his fallen mentor, whose motives are as murky as the mission itself – Hunt is left with nothing but his wits, a few gadgets, and a deep-seated trust in no one. He races to unmask the real traitor and survive a world where nothing is as it seems.

For fans of the original Mission: Impossible TV show – where Peter Graves’ Jim Phelps led a team of experts through intricate missions and out of impossible corners – the film opens with a bait and switch that borders on heresy. The ensemble’s all there… briefly. Familiar faces like Kristin Scott Thomas and Emilio Estevez give the impression we’re settling in for a sleek, star-studded team thriller, but it’s smoke and mirrors from the start. Much like the show’s legendary cold opens, we’re given the illusion of a familiar setup only to watch it collapse in real time. The film’s real sleight of hand isn’t just in the masks and moles – it’s structural. This Mission doesn’t just revise the format. It burns the playbook and builds something new in the ashes.

What De Palma and Cruise (in his first real producer flex) engineer here is less a straight continuation and more a rebirth. It’s a cinematic version of the tape that self-destructs: the past is acknowledged and honoured, but deliberately discarded. By turning Jon Voight’s Jim Phelps – the avatar of old-school teamwork – into the villain, they set out the film’s boldest move: this is no longer a series about the team. It’s about the man. Ethan Hunt is the new face of the Impossible Missions Force, and Cruise ensures you never forget it by throwing himself into each stunt with what appears to be an insurance policy underwritten by unshakable Operating Thetan Level VIII confidence.

When the restaurant explodes in a spectacular deluge of glass and trout, it’s less a stunt than a baptism – Cruise, reborn as the star who’ll do anything to sell a moment. Whether it’s in glass, rain, or sweat, Cruise seems to genuinely believe water adds dramatic heft – and you know what? He’s not entirely wrong. It’s part of the film’s obsessive dedication to making Ethan Hunt suffer spectacularly, and part of the actor’s now-legendary fetish for realism, pain, and velocity.

The running, of course, is a whole other matter. This is where it began – the kinetic, arms-pumping, soles-slapping dash towards greatness. Cruise’s commitment to cardio might be Hollywood’s most reliable special effect, and Mission: Impossible sets the template: no matter the odds, Ethan will run. Through Prague. Across rooftops. Down corridors. Possibly through plot holes. Always forward, never flinching.

While later entries would fine-tune the franchise into sleek adrenaline machines, the original Mission: Impossible remains a curiously earnest concoction – slick but slightly stilted, punchy but puzzled about its own tone. It leans into the cerebral paranoia of the Cold War even as it gears up for the stunt-fuelled fireworks of the digital age. Danny Elfman’s atypical score dials back his usual flair for the macabre in favour of something leaner, colder, more covert – tense and percussive, but unmistakably his. Lalo Schifrin’s iconic theme still anchors the soundscape, but it’s U2’s Larry Mullen Jr. and Adam Clayton who drag it into the ‘90s with a pulse-quickening remix that blasts the franchise into the pop-cultural bloodstream before the fuse has even burned down. The tech – by ’90s standards – is both absurd and charmingly lo-fi. Diskettes, floppy drives, chewing gum explosives. Retro-futurism before it was fashionable.

There’s a constant tension between homage and evolution. The masks remain – as do the tape recorders and voice changers – but the pacing, stakes, and style shift dramatically. The original show thrived on patience and planning, built around watching competent professionals outwit dictators and despots. This Mission trades that slow-burn sophistication for panic and propulsion, where the masks are only skin deep and trust is a liability. It’s the difference between watching a master thief pick a lock and watching a movie star brute force the door with a sledgehammer. Both are entertaining, but only one is going to sprint the length and breadth of downtown Prague to do it.

Mission: Impossible was never expected to become the juggernaut it would eventually turn out to be. At the time, it was Cruise’s most expensive production – a risky resurrection, a nostalgic brand name slapped onto a genre film with ambitions far beyond its remit. That it worked – that it launched what’s now one of Hollywood’s most consistently inventive franchises – is a testament to just how clearly the film understood what needed to be kept, what needed to be jettisoned, and how hard its star was willing to work to make it happen. The mission was on, even if it would take a couple more assignments before it achieved the impossible.