The future’s so white, we gotta wear shades.

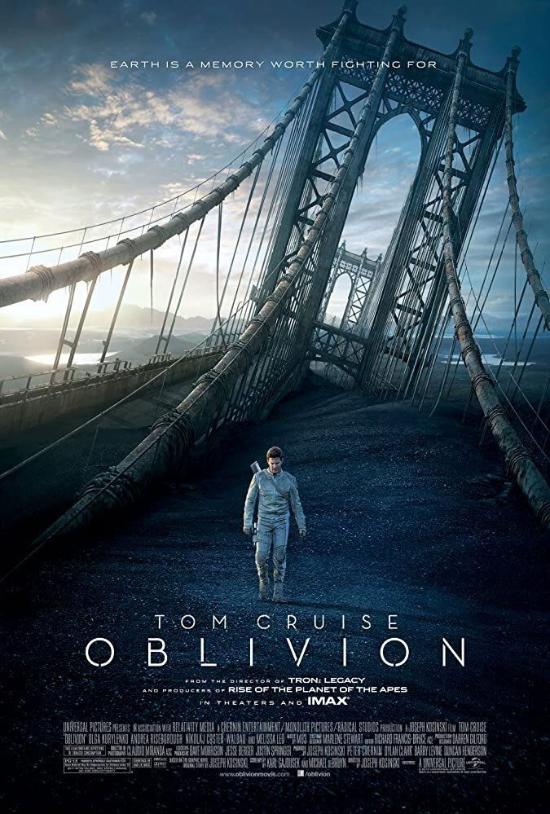

Tom Cruise lives in a house that could’ve been designed by Kubrick’s interior decorator and Apple’s industrial design team during a silent retreat on the Moon. Suspended above a decimated Earth, the glassy tech-bubble he shares with Andrea Riseborough’s buttoned-down handler feels like the kind of luxury Airbnb you’d book without checking into further just because it had a cool-looking pool. This is Oblivion, a film as fascinated by the aesthetic legacy of science fiction as it is by the grand existentialism of identity, memory, and purpose – albeit refracted through a distinctly Cruise-shaped lens.

Joseph Kosinski, whose affinity for architecture and aviation seems written into his cinematic DNA, directs with the obsessive precision of someone arranging a pristine model kit of other, greater sci-fi films. The difference is that Oblivion doesn’t just wear its influences – 2001, The Matrix, Moon, WALL·E, and more – it models them like tailored suits. It’s not homage-as-plagiarism, nor is it homage-as-empty-reference. It’s more like a DJ set, carefully mixed for mood and texture, where recognisable samples are stitched into something sleek, sincere, and oddly affecting.

Cruise, as Jack Harper (Tech 49, if we’re being formal), is in autopilot mode only in the sense that he’s piloting actual drones and bubble-ships. The performance is classic late-stage Cruise: kinetic, noble, a touch haunted. But Oblivion affords him more stillness than usual, and he uses it well, while the sci-fi setting limits his capacity for headling-grabbing stuntwork so he has to act his way through rather than just perform. Jack’s curiosity – a trait treated with mild exasperation by Riseborough’s Victoria – becomes the seed of everything that follows. And while the character isn’t especially complex, the way Cruise plays him against the sterile environment gives just enough grit to stop the film sliding off the smoothness of its surfaces into the uncanny valleys of its inspirations.

It helps that the film trusts its silences. Anthony Gonzalez and M83’s score pulses with electronic melancholy, wrapping scenes in an ambient hum that’s part synth elegy, part space-age hymn. It’s not a noisy movie, despite its action set-pieces, and that quiet confidence elevates what could have been a high-concept patchwork into something more contemplative. Oblivion shares more DNA with Silent Running, Solaris, THX 1138 or even Logan 5’s exploration of the forgotten world outside the City in Logan’s Run than it does with its louder contemporaries. The drone battles, while crisply staged, aren’t the main event. It’s the way Jack stands among the ruins, fingers brushing old paperbacks and rusted remnants of a forgotten humanity, that gives the film its thematic weight. For all its gadgetry, Oblivion is about ghosts.

Riseborough does far more than her character’s clipboard-and-coffee role suggests. Her Victoria is icy, yes, but there’s a desperation beneath her surface-level compliance that makes her eventual unraveling quietly devastating. Olga Kurylenko’s arrival as Julia threatens to tip the balance into melodrama, but the film skirts the worst of it by keeping things enigmatic. Even Morgan Freeman, sporting his well-worn “sci-fi mentor” chapeau, seems to recognise he’s there to lend mythic weight more than move the plot. He obliges with the requisite gravelly gravitas and a cigar, which at this point may as well be a wand.

What Oblivion lacks in narrative novelty it makes up for in execution. The plot turns aren’t exactly shocking if you’ve spent any time in sci-fi cinema, but the film’s approach is so polished – so committed in its desire to craft something beautiful out of old parts – that the predictability feels almost comforting. It doesn’t bluff its way through its twists; it lays its cards out with a kind of cinematic grace, letting the audience feel clever for keeping up rather than attempting to outfox them.

It’s also one of the few modern blockbusters that genuinely understands scale. Earth isn’t just a backdrop – it’s a hollowed-out character. Monument Valley is a recurring motif, and Kosinski shoots it like sacred ground, not tourist wallpaper. The derelict landmarks, half-buried in ash or sand, aren’t there for cheap irony or visual shorthand. They’re artefacts of loss, reminders that even global cataclysm might not entirely erase the cultural detritus we leave behind.

If Oblivion has a flaw, it’s that its elegance sometimes strays into sterility. The romance subplot never quite sparks, and the emotional beats land more softly than they should. But even that coolness feels deliberate – a tonal decision to keep things restrained, measured. It’s sci-fi as mood piece, a high-concept dream half-remembered from a thousand other films but rendered here with uncommon finesse.

Kosinski would go on to re-team with Cruise to deliver crowd-pleasing popcorn adrenaline with Top Gun: Maverick, but Oblivion remains a more interesting calling card: a big-budget sci-fi film content to be quiet, composed, and a little opaque. It doesn’t shout for attention – it elides. A remix of classics, yes, but one played with vinyl warmth and headphone intimacy. Not every original is worth more than its influences. Sometimes, the remix is the better listen.