Home is where the heartbreak is.

The most ruthless and remorseless battle of the sexes ever committed to film doesn’t erupt in a courtroom or therapy session. It plays out in a kitchen, a hallway, a home sauna – inch by bloody inch of shared property turned into a theatre of conflict. The War Of The Roses masquerades as a romantic drama for its first act, but by the time the emotional trenches are dug and the divorce papers drawn, it’s clear there’s nothing civil about this war. It’s unflinching, unrepentant, and almost entirely devoid of relief. The only catharsis on offer is a grim chuckle in the closing seconds – gallows humour clinging to the wreckage.

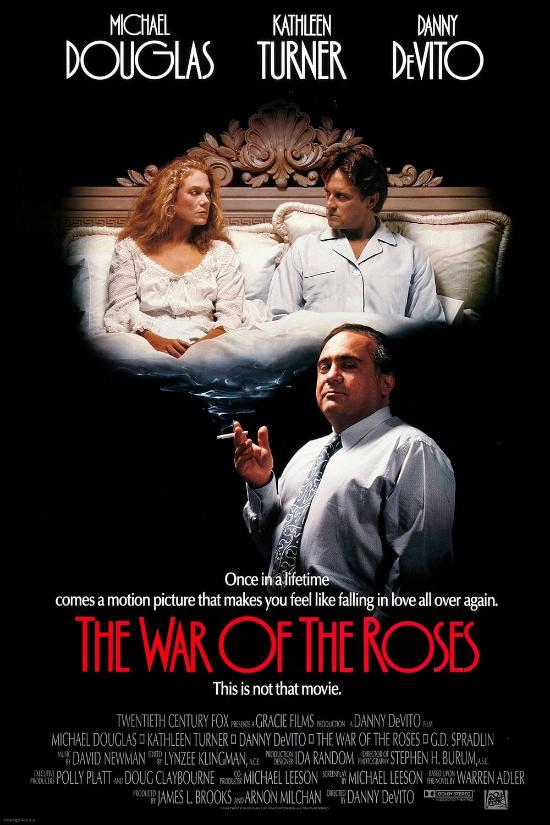

By 1989, Michael Douglas and Kathleen Turner had already proven their chemistry in the high-adventure excess of Romancing The Stone and the loose-limbed, slightly boozier The Jewel Of The Nile. What makes The War Of The Roses so startling is how deliberately it sets out to subvert that chemistry. It doesn’t just set aside the romantic arc of those earlier films; it surgically dissects it; a relationship vivisected on the autopsy table. There’s no reconciliation, no wistful clinch in the rain. Just the same two performers, now turned against each other with acidic malice, daring the audience to keep rooting for a happy ending that never comes. It’s a bleak, barbed inversion of everything their previous pairings delivered – and all the more brilliant for it.

Douglas, who’d made a fine art out of playing men unravelling under pressure, delivers one of his most ruthlessly sharp performances as Oliver Rose: smug, successful, and completely incapable of understanding the storm he’s helped engineer. He enters the story believing he’s the wronged party in a noble cause, but ends it diminished, petty, and impossible to absolve. His performance teeters brilliantly on the edge of caricature, but never falls. Turner, liberated from playing anything remotely like a love interest, detonates with cold fury and withering control. Her Barbara Rose is not unhinged or irrational; she’s simply incandescently unwilling to continue being taken for granted. She doesn’t play the femme fatale – she plays the realist who realises too late that escape requires scorched earth.

There is no protagonist here. No side worth cheering for, just two antagonists determined to antagonise each other. The film doesn’t offer perspective so much as a coroner’s report on the death of a marriage. You’re locked in the house with them, bearing witness to the fruits of love rotting on the vine. DeVito’s Gavin, the lawyer with a front-row seat, acts as a kind of weary archivist. His narration doesn’t guide or reassure – it merely catalogues the downfall. He isn’t above it, just unlucky enough to have been caught up in the gravity of it.

As director, DeVito finds a different gear from the anarchic energy of his debut feature Throw Momma From The Train. Here, his touch is sharper, more deliberate, bleaker. He lets the curdling of the relationship do some of the talking, and suppresses his comedic instincts, channelling them into something dark and bitterly ironic. It revels in the discomfort, and the only laughter on offer is the nervous kind.

Despite the eventual comic carnage, this is a film about divorce as tragedy; the decay of love in the face of pride, resentment, and unyielding ego. It’s about how the law, and the property ladder become weapons when both parties refuse to surrender anything, even the illusion of control. The sparse comedy is beyond pitch black, and never smug. It doesn’t mock the characters as much as reveals them. Neither Oliver nor Barbara is a villain, but neither is a hero either. It’s the ultimate ‘hurt people hurt people’ movie where the escalating viciousness finds its origins in the banal ordinariness of neglect and complacency.

That Turner and Douglas commit so fully to the bitterness makes the dramedy richer without becoming meaner. Their willingness to disgrace their characters for laughs and despair alike recalls Tracy and Hepburn if you drained out the affection and replaced it with resentful entitlement. It helps that they’re perfectly matched in timing, posture, and the silent rage of cohabitation. This isn’t an escalation into absurdity for the sake of farce. It’s entropy, rendered with such methodical glee that even the audience starts to feel trapped inside the house; inside the disintegrating marriage. By the final moments of the film, we’ve left drama and even comedy behind and strayed into psychological horror. A home invasion turned in on itself, a home inversion if you will: home is where the heartbreak is.

As the final reunion of the Turner-Douglas-DeVito trifecta, it is perversely perfect. Not because it completes some sentimental arc, but because it finds a nastier kind of synergy, one free of genre expectations and character archetypes. It shows what happens when you give three performers who know each other’s rhythms inside out the freedom to turn that familiarity into friction.