Powerhouse performances struggle to breathe in all the stuffiness.

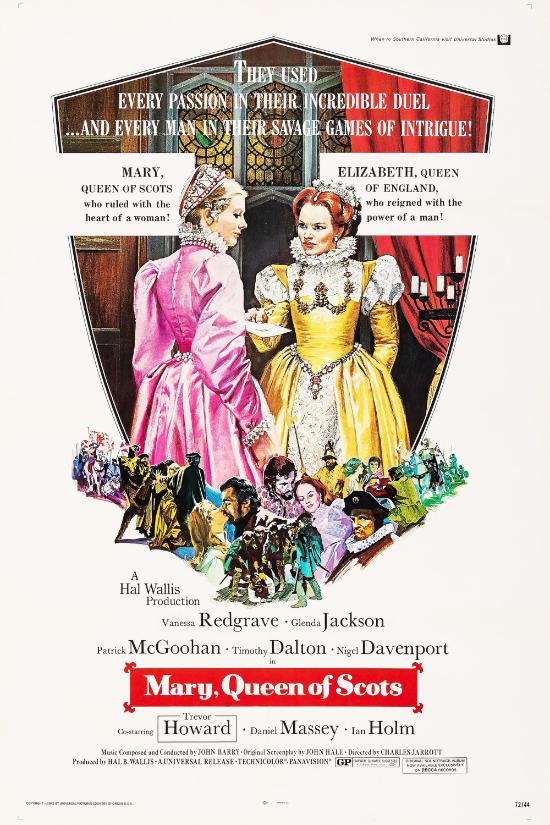

Historical dramas of the 1970s had a particular flair for the grandiose, and Mary, Queen of Scots stands as one of the most polished and theatrical of them all. Directed by Charles Jarrott, the film brings a stately, almost Shakespearean air to the tragic story of Mary Stuart, a monarch doomed by love, politics, and miscalculation. As played by Vanessa Redgrave, Mary is noble, passionate, and naive, a woman swept up in forces beyond her control. Across the channel, Glenda Jackson’s Elizabeth I is her opposite: calculating, pragmatic, and ever-conscious that ruling as a woman requires sacrifices Mary never seems willing to make.

For all its costume-drama splendour, this is first and foremost a film about rivalry, and it plays out like a game of regal chess, with both queens making moves and counter-moves from afar. The historical liberties taken – most glaringly the invented meeting between Mary and Elizabeth – aren’t subtle, but they serve to crystallise the film’s central conflict in a way history never allowed. The real Mary and Elizabeth never met, but Mary, Queen of Scots frames their relationship as one of personal antagonism rather than political circumstance, and it’s all the better for it dramatically.

Redgrave plays Mary as a queen led by her heart rather than her head, a woman determined to rule but unwilling to wield power with the ruthlessness it requires. Her scenes with Timothy Dalton’s Lord Darnley crackle with intensity, as do those with Ian Holm’s devious John Knox, but the film’s greatest pleasure lies in the war of words and wits between its two leads. Jackson, fresh from her Elizabeth R TV triumph, brings an authoritative presence – her Elizabeth more warrior than woman, dismissive of Mary’s insistence on dynastic entitlement.

The film is lavish, though in a way that now feels somewhat stage-bound. The cinematography leans into the rich tapestries and heavy velvet of the Tudor and Stuart courts, emphasising the weight of history pressing down on both queens. The sweeping landscapes of Scotland are contrasted with the enclosed, almost oppressive interiors of Elizabeth’s England, reinforcing Mary’s increasing isolation.

The pacing takes its time unfurling Mary’s downfall, and while this allows for some beautifully played moments, it also means the energy dips just when it should be ratcheting up the tension. There’s also a distinctly 1970s approach to historical storytelling at play – romanticising Mary’s decline in a way that leans more towards melodrama than political tragedy, smoothing over her missteps and ignoring the harder truths of her character.

Still, as a sweeping, old-school historical epic, Mary, Queen of Scots delivers all the grandeur and tragedy one could want. The performances alone elevate it beyond a conventional period piece, with Redgrave and Jackson ensuring that Mary and Elizabeth’s battle for dominance is one for the ages – even if, in reality, it was fought through letters rather than direct confrontation.