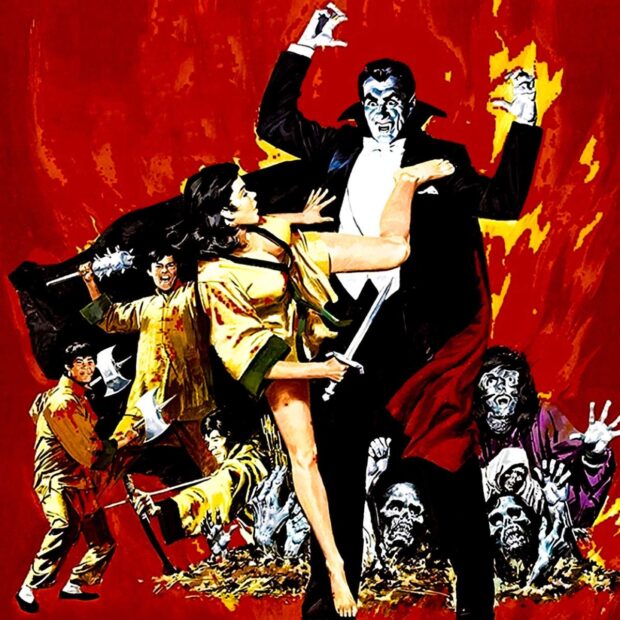

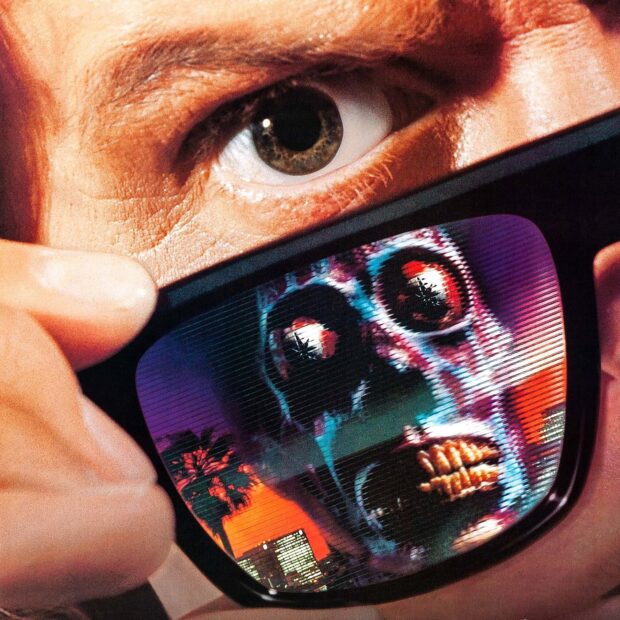

A who’s Who of Horror iconography.

The House That Dripped Blood may not live up to its sanguine title, but what it lacks in claret, it makes up for in genteel gothic ambience and a worthy addition to the anthology format Amicus made their calling card. Released around the middle of Amicus’ ten year run of horror anthologies, this four-part showcase of creeping dread and psychological unravelling wraps itself in cobwebs and dribbly candle wax, a celebration of waxy complexions, waxier effects and the ominous creak of antique furniture with a guilty conscience. Penned by Robert Bloch (yes, Psycho’s Robert Bloch), the film parcels out its thrills with a knowing smirk and a fondness for the uncanny, all loosely held together by a framing story that barely pretends it isn’t just killing time between set-pieces.

Inspector Holloway (John Bennett) arrives at the titular house to investigate the mysterious disappearance of a horror actor and from that framing story, the film unfurls its quartet of creepiness. The tone may shift between the eerie, through tragic to gleefully absurd but its anchored by Bennett’s detective’s guided tour through the house’s greatest hits.

First out of the gate is Method For Murder, where Denholm Elliott – always a welcome addition to any cast – gets to do double duty as both a writer and the snarling killer Dominick who steps out of his mind and, via the page into the real world, murderously and improbably incarnate. It plays like a prototype for The Dark Half, years before King put pen to paper to exorcise his own demons, and Elliott handles the split with a precise, understated relish and while the twist is hardly gasp-worthy, it earns its place with a pulpy charm.

Waxworks follows, with Peter Cushing doing what Peter Cushing does best: stepping into danger with an understated mournfulness. He plays a lonely bachelor who visits a wax museum and is haunted by the eerie resemblance of one of the figures to a woman from his past. As the pull of nostalgia grows stronger, he returns again and again, each time slipping further into melancholic obsession. When an old friend follows in his footsteps, the exhibit’s sinister enchantment claims another victim. It’s the most lugubrious of the four stories, leaning hard into themes of mourning and memory, with Cushing channelling quiet heartbreak beneath his usual reserve.

And as if by dark magic, Cushing hands off to his oft-time horror collaborator as Christopher Lee headlines Sweets to the Sweet, a sugary confection of simmering witchcraft and family drama with Lee in archly disciplinarian parent mode, locking horns with his young daughter over some very mysterious restrictions. It’s the creepiest of the four, with Lee’s tightly buttoned terror suggesting a man who’s convinced himself he’s doing the right thing even as the doubts start to rise. The twist may be signposted from the first few minutes, but the segment works thanks to Lee’s commitment and the eerie stillness of Chloe Franks as the unnervingly precocious child.

Finally, The Cloak brings in Jon Pertwee and Ingrid Pitt to knock the dust off the drapes. Pertwee, clearly relishing the chance to play a pompous horror star with a fondness for authenticity, is all flounce and baritone as he discovers a cloak with mysterious powers but it ups the ante when Pitt wafts in like the horror Grande Dame she is, a gothic galleon in full sail and showing everyone how campirism should be done. The whole segment plays close to being an affectionate self-parody of the genre and the format without diminishing either.

It helps enormously that director Peter Duffell never lets the production tip over into outright camp and the film’s theatricality is balanced by a genuine affection for its subject matter. While the house may not be exactly dripping blood, it is soaked in genre gravitas, and Duffell treats it as both a stage and a trap.

Sure, it’s uneven (most anthology films are) and Waxworks could have lost a few drips of melancholy without anyone noticing, but the mix of tones and the gallery of genre greats keep things moving. There’s little in the way of gore or explicit horror, but that’s not what The House That Dripped Blood is aiming for. It wants to get under your skin the old-fashioned way, through suggestion, shadow, and the slow tightening of atmosphere.