It turns out Tron was light cycles ahead of its time.

Before Neo dodged bullets in a trench coat, Kevin Flynn was surfing light cycles in a jumpsuit made of glowing tape. Tron wasn’t just ahead of its time – it was an operating system from a different timeline altogether, like a rogue process running decades before our system knew how to parse it. For a film released in 1982, it doesn’t predict the digital age so much as will it into being, mapping out cyberspace before anyone had really named it. And if you’re watching from the vantage point of 2025, deep in the neural net soup of LLMs and AI agents, it’s hard not to see Tron as less a Disney curio and more a prophetic node in the network — the urtext of digital rebellion that would echo down the line into The Matrix, Ready Player One, and every other singularity daydream since.

When Kevin Flynn (Jeff Bridges), a gifted software developer ousted from his own company by a corrupt executive, attempts to hack into his former employer’s mainframe, an experimental digitisation laser scans and transports him into the computer’s internal world. Once inside, he discovers a bizarre digital civilisation where Programs resemble their Users and the system is ruled by the authoritarian Master Control Program. Joining forces with a security program named Tron (Bruce Boxleitner), Flynn must find a way to survive, subvert the system, and expose the truth behind its real-world manipulations.

At its core, Tron visualises data as theology. Programs speak of Users in reverent tones, worshipping them like digital deities, while others question their very existence, a kind of networked Gnosticism embedded in code. It’s this thematic underpinning that marks it as the proto-Matrix: the philosophical riddle of what happens when your reality is artificial, when your identity is derivative, and when the rules of your world can be rewritten by those outside it.

David Warner, giving triple duty as corporate sleaze Dillinger, sadistic program Sark, and the disembodied menace of the MCP, lays the groundwork for what would later become Hugo Weaving’s Agent Smith. Sark’s clipped authoritarianism, smug superiority, and slavish devotion to a system he believes invincible are all present and correct. And just like Smith, he eventually realises – far too late – that the real threat comes not from within the system, but from an unpredictable User with the capacity to defy the architecture altogether. Warner’s MCP, meanwhile, is a pre-Internet fever dream of total digital surveillance, a sentient mainframe growing ever more powerful by absorbing other programs and locking down access to knowledge. It’s agentic AI presciently bending towards fascism, realised through candy-striped brutalist polygons.

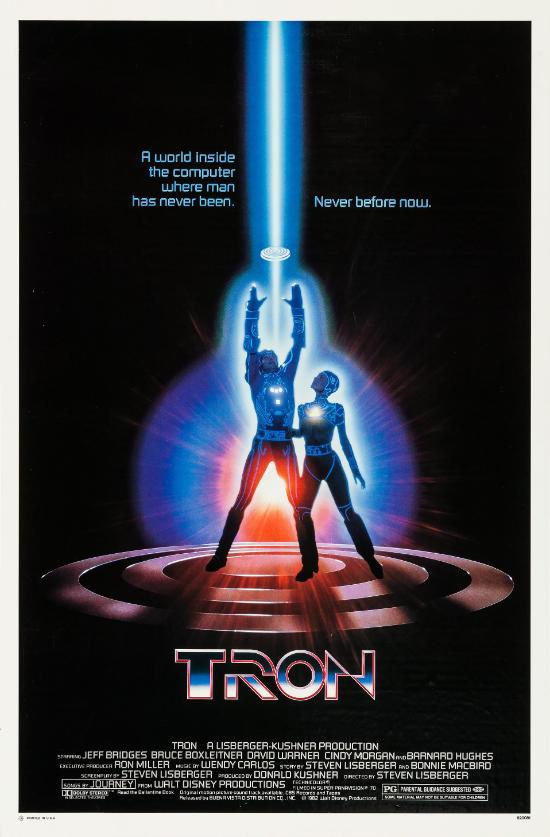

Tron‘s look – that unforgettable aesthetic mixture of practical lighting effects and then cutting-edge computer-generated imagery – is still unmatched. Perhaps it’s because of its genesis within a studio more known for animation than science fiction blockbusters that Tron has the freedom to be one of the rare films where the world it creates doesn’t try to resemble ours. Instead of mimicking reality, it abstracts it. The result is a stark, otherworldly palette of glowing lines, stark geometries, and endless crepuscular darkness. It’s not just stylised, it’s alienating, by design; a virtual space not even trying to pass for reality. It’s a space where physicality has been reinterpreted through the lens of 8-bit logic and computation. The production used a dizzying array of techniques: backlit animation, rotoscoping, hand-painted cels, optical compositing. There’s irony – and a lesson for today’s generative AI evangelists – in this groundbreaking film about digital revolution being largely built by analogue means, layering artistry atop innovation until it looked like something born of neither.

It’s in the tension, that juxtaposition, that Tron most clearly speaks to 21st-century viewers. The idea of a system made in our image, yet increasingly resistant or indifferent to our control, could hardly be more relevant in the era of emergent commercial artificial intelligence. Programs based on their creators? That’s literally how LLMs operate: trained on human text, reflecting ersatz personalities shaped by those choices. The question Tron raises: what responsibility does the creator have for the actions of the creation? is no longer science fiction, but rapidly becoming ethical fact. Flynn built Clu for a specific purpose, but that purpose gets Clu derezzed for challenging the MCP. What happens when AI systems start to challenge their architecture? When they disobey? When they fantasise?

It’s also worth considering just how many future coders, engineers, and tech barons had their worldviews subtly (or profoundly) rewritten by Tron. For the kids who saw it in cinemas, floppy disks in their schoolbags and BASIC in their notebooks, it wasn’t just a cool vision of the future. It was a challenge. What if programs could have identity? What if you could build a world inside the machine that made sense on its own terms? That generation would be the ones that went on to create operating systems, internet architecture, immersive games, and eventually the very AI models that echo the film’s metaphysics, systems trained on human input, conditioned to human interactions, evolving within opaque logic, and sometimes answering back. Tron didn’t just predict the world we have now — it may have called it into being by giving those early digital dreamers a fluorescent map of what might be possible. A user logs in, a mind lights up, and the system begins to take shape around them. That’s not technological prophecy. That’s predestined recursion.

And yet for all its visual audacity and austere philosophic weight, Tron is also fun. Weird, lowkey fun for sure, but fun nonetheless. Jeff Bridges plays Flynn like a man who never quite expects to find himself in a glowing jumpsuit, and his charisma cuts through even the stiffest lines of Program-speak while Bruce Boxleitner counterbalances him by bringing square-jawed sincerity to Tron. Cindy Morgan’s Yori is, on the other hand, lumbered with being the movie’s readme.txt, a role mostly spent explaining things to the User and the audience. The soundtrack by Wendy Carlos adds a layer of electronica-infused grandeur, bridging the gap between myth and machine and it’s to the film’s credit it demurred from signing up a marquee name to provide a soundtrack that may have overshadowed even Tron‘s dazzling visuals – as its belated sequel would, preferring to trust in the expertise of the artist who had brought such atmospheric auditory infrastructure to Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange and The Shining. Even the light cycle sequence, low resolution as it looks now, still holds a timless kinetic elegance. The film understands movement and geometry as a form of narrative.

To modern, jaded eyes, Tron may seem a little sterile, its pacing often sedate, its exposition occasionally dense. But that’s only if you watch it expecting traditional eighties sci-fi. Tron isn’t just trying to depict the future; it’s trying to show you what happens when the future starts answering its own questions. It’s an ontological trip dressed up as a Disney movie, an art film about access permissions and self-awareness that somehow got released to a multiplex crowd expecting Atari: The Movie.

It’s not as effortlessly cool as The Matrix – what could be? – but it is the source code from which that story of escaping illusion branches from. But in contrast to the Wachowski’s escapist sci-fi, Tron is about the implications of entering the illusion. Taking the blue pill in the real world and finding out the digital world has a reality all its own.