A life well lived.

If you’re going to take the apocalypse personally, The Life of Chuck makes a compelling case for throwing a goodbye party complete with a dance number and a cosmic flourish. Based on the novella from Stephen King’s 2020 collection If It Bleeds, it’s a rare entry in the canon of King adaptations: metaphysical, tender, and almost entirely devoid of horror. Mike Flanagan, continuing his long-running conversation with King’s work, delivers his most delicate and formally daring adaptation to date; a love letter to existence that eschews the usual genre tropes and goes straight for something stranger, smaller, and infinitely more ambitious.

Built in reverse, structurally and emotionally, The Life of Chuck begins with the collapse of everything and ends with the quiet joy of acceptance, not in defiance of storytelling logic but in quiet homage to poet Walt Whitman’s tender deconstructions of who we are. Flanagan disassembles the timeline of a man’s life like he’s winding back a watch, not for nostalgia’s sake but for narrative lyricism. This isn’t a twist-driven mystery box or a gimmicky time-reversal trick, it’s a deeply sincere invocation of how meaning accrues not in forward momentum but in memory, impression, and connection. Each segment peels back a different layer of Charles Krantz, not to explain him but to honour the unknowable machinery of a life lived, the mosaic of contradictions and quiet affirmations that feel lifted straight from Whitman’s Song of Myself, where contradiction isn’t a failing but a virtue; a diversity of being. It’s an idea King has toyed with time and again across his career, but rarely with such minimalist and tender focus.

Tom Hiddleston plays Chuck with a kind of luminous restraint, the kind of performance that reassures and rewards stillness. He doesn’t over-signal trauma or revelation; he lets Chuck emerge in fragments and figments, a man we come to know by the shape of his absence as much as his presence. The entire cast seems calibrated to the same frequency: Karen Gillan’s Felicia and Chiwetel Ejiofor’s Marty feel like people caught mid-thought, half-aware they’re merely players in someone else’s story and even the younger iterations of Chuck (Jacob Tremblay, Benjamin Pajak, Cody Flanagan) contribute something substantial but intangible that sticks in the mind, like a feeling of déjà vu that’s finally explained.

The film’s flamboyant heart – a five-minute impromptu life-changing dance sequence – is both the showiest and yet quietest moment of Flanagan’s career. It’s joyous, audacious and intoxicating, not just for its smoothe choreography but for its emotional clarity. There’s not a shred of ironic self-awareness on offer, just people moving to the rhythm that’s moved them. It’s maybe the closest American cinema has come to a Miyazaki moment without resorting to animation: serene, spellbinding, and defiantly gentle.

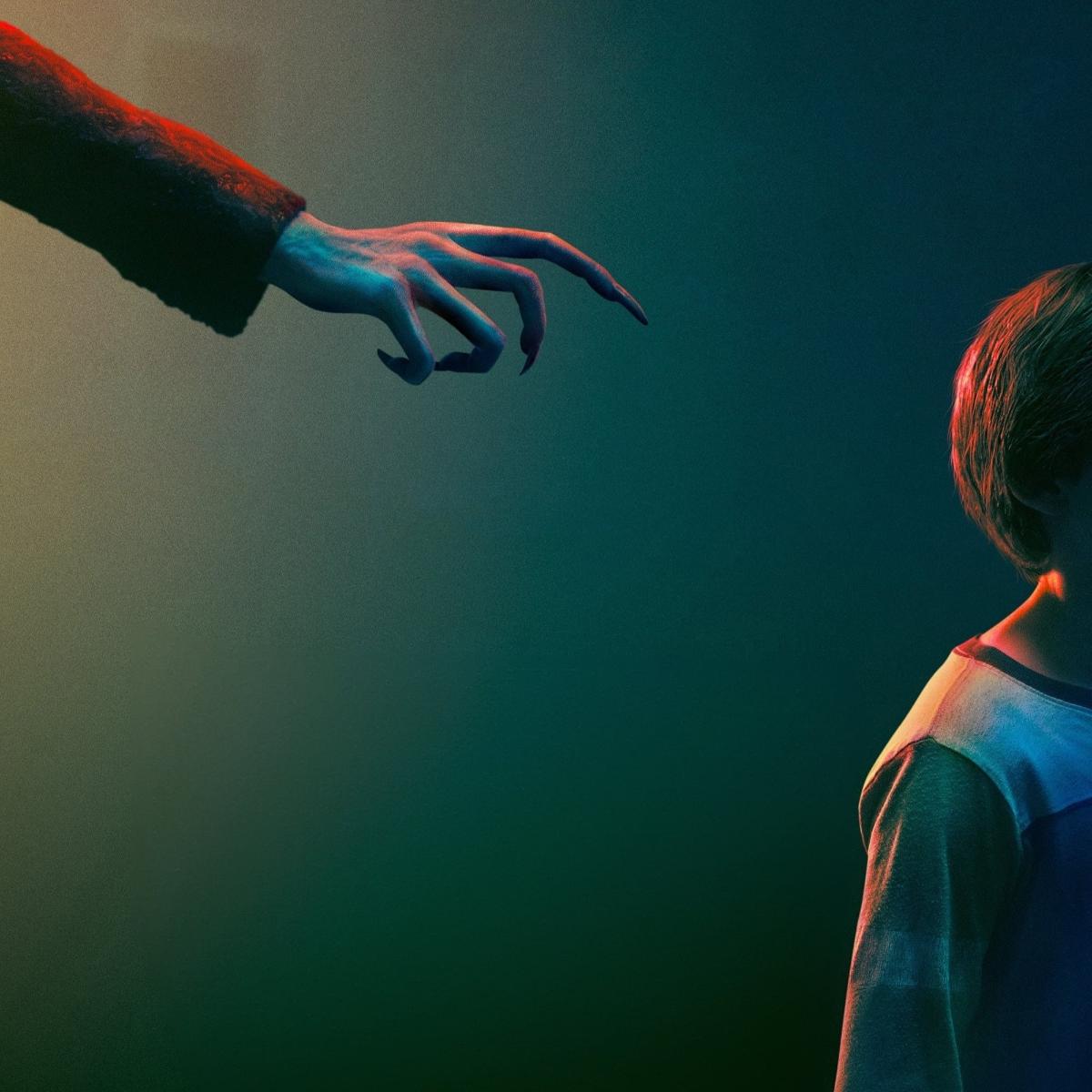

As with much of Flanagan’s recent work, The Life Of Chuck is a story fascinated by liminal space, perhaps the ultimate liminal spaces: the veil between life and death, love and grief, self and other. But unlike Doctor Sleep or Midnight Mass, it doesn’t lean on horror to get there. There are no monsters here, only rose-tinted mirrors. The end of the world isn’t a spectacle, it’s a metaphor, but one that never tips into parable. When reality begins to glitch – WiFi gone, sinkholes blooming like bruises, billboards blaring Chuck’s retirement like the world’s trying too hard – it’s played not for panic but for poignancy. The fabric of the universe isn’t unravelling in fury and we’re not raging against the dying of the light, we’re just letting go, in peace.

Flanagan’s use of the frame is quietly radical, trusting in silences and letting absurdities linger without comment or context. There’s no rush to reassure, no quest to clarify too much too soon. The inverted structure could have been a cold intellectual exercise, or a reverse Forrest Gump saccharin slog but it isn’t. It’s graceful, earned and by the time the denouement arrives, chronologically last but narratively first, it feels like resolution rather than revelation.

For a story that few might have seen the big screen potential in, The Life of Chuck reaffirms the breadth and depth of King’s storytelling domain. So often reductively referred to as the master of horror, King here proves (yet again) that his real fixation is mortality, in all its myriad manifestations; how we face it, how we remember, how we find light at the edges of the dark. It’s a thematic thread that connects The Life Of Chuck to Stand By Me and The Shawshank Redemption, two of the most enduring King adaptations, with neither of them reliant on the supernatural. The Life of Chuck earns its place alongside them, not by imitation but by inclination, a shared understanding that life is the strangest magic of all.

For a collaboration between a filmmaker and an author both so comfortable with the darker aspects of death, The Life of Chuck is unexpectedly full of life. It understands something few films ever really try to articulate: that our stories aren’t defined by how they end, but by who remembers them, and how they’re experienced.