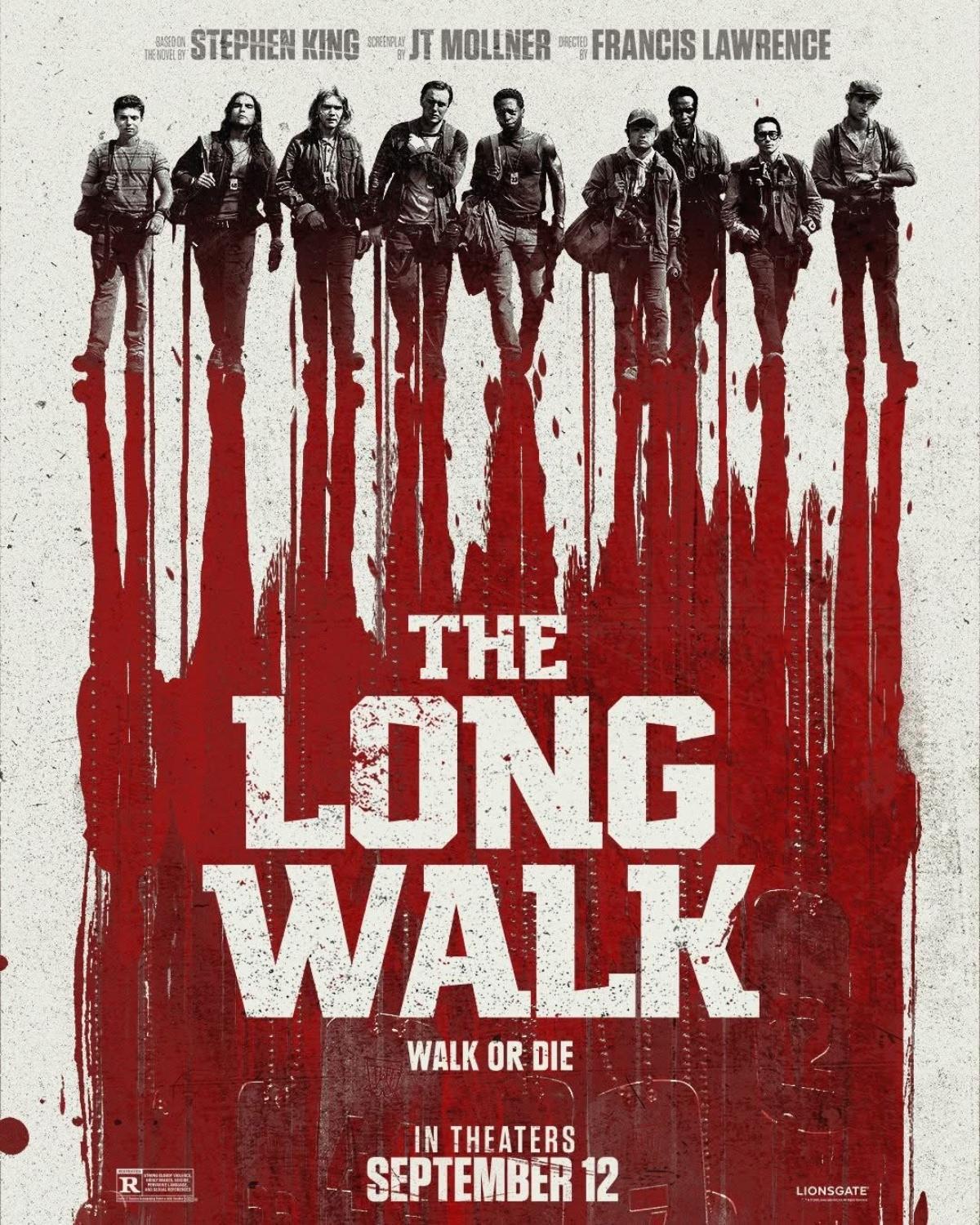

It may be the journey, not the destination that matters but The Long Walk punishes both.

They say ‘the journey of a thousand miles starts with one step’ but in The Long Walk, after you take that first step, the journey will take the rest of your life. There’s a brutal simplicity to the premise, compounded by a chilling plausibility, as we watch America’s youth trudge their way to oblivion for the sake of propaganda.

Set in an alternative post-World War II America, where the war did not end well for the land of free and the home of the brave, as it collapsed economically and politically into a military dictatorship. The hard times have bred hard men, and harder entertainment; an annual compulsory competition where every state is required to send a competitor for an endurance race where the winner takes all and the only prize for the also-rans is a bullet to the head.

Francis Lawrence, veteran of multiple Hunger Games movies, is no stranger to a post-collapse America twisted into dystopian parody and held together by the collective delusion of a unifying gladiatorial contest but here he – and his regular collaborators Jo Willems on cinematography and Mark Yoshikawa on editing duties – pare the world back to what matters: the road, the roster and the relentless march. It’s a world away from the stylised extremes of Panem, but The Long Walk isn’t revolution cinema. It’s resigned collapse, a slow-motion slog through a world without a shred of hope.

There’s no overt rebellion, no messianic Mockingjay analogue waiting in the wings. That’s what makes the realisation of the premise so much bleaker. The terror isn’t institutional oppression with a glimmer of hope. It’s institutional apathy perfected. Few attempt to flee. Fewer still question. They walk – until they can’t physically walk anymore and it’s in that obedience the story finds its most intimate and insidious dread.

The adaptation makes smart structural changes without compromising the marrow of the original novella. It halves the number of walkers from 100 to 50, aligning each one with a U.S. state to emphasises the ghastly patriotic sheen and cruelly give us more time to come to know and bond with the walkers, despite the inevitable outcome they and we know must follow. It’s a harder lean into nationhood-as-pantomime than the source ever did, and the result is unnervingly effective in an age where politics has become the ultimate reality show and a game show host is commander-in-chief.

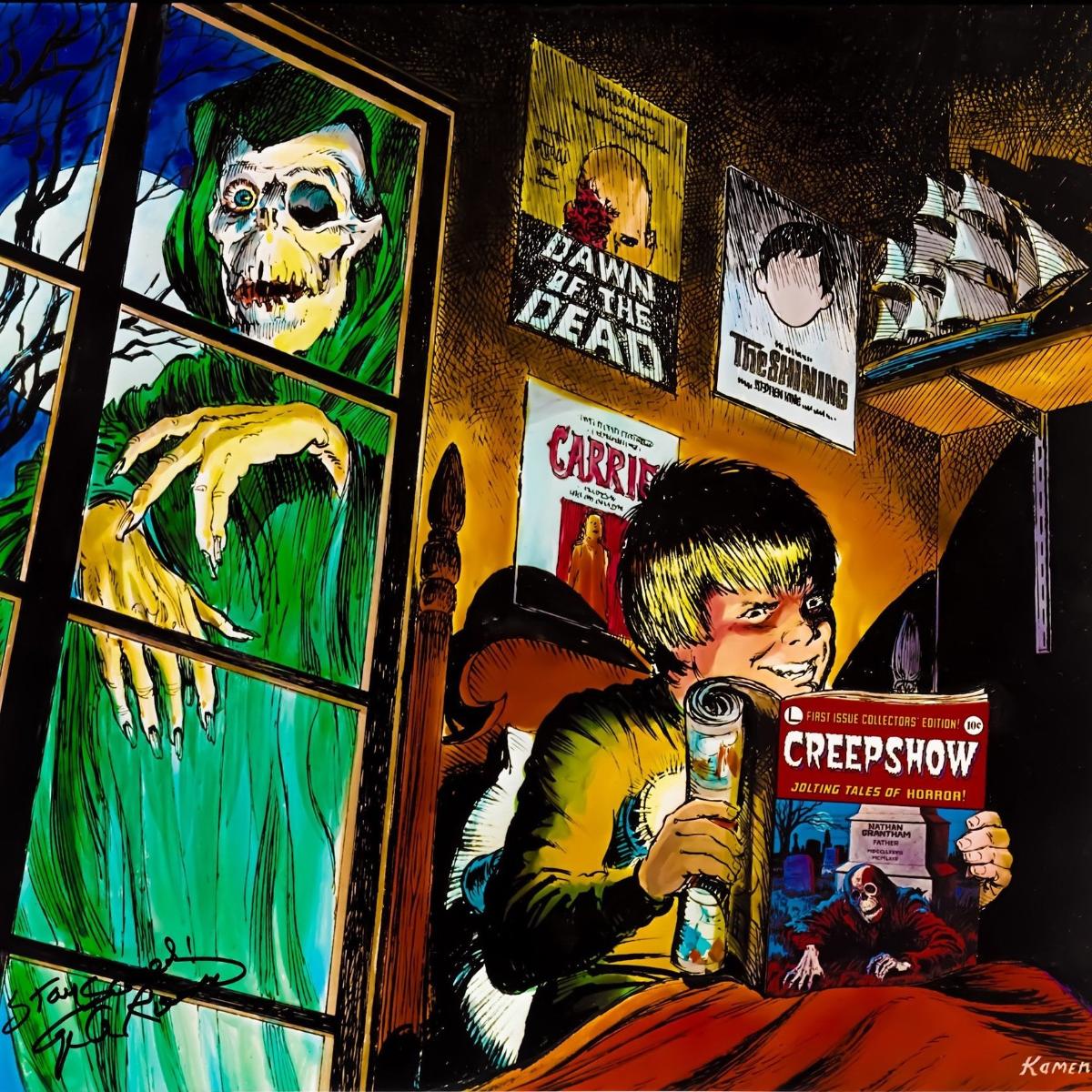

Of all King’s dystopias, this one always felt the most probable. Not just because of the idea of a state-sanctioned death march performed as national entertainment, but because of how little effort the society within it puts into justifying its existence. The rules are simple, and strictly enforced. There are three warnings but no second chances. And despite that simplicity, or maybe because of it, The Long Walk thrives. It builds itself not through incident, but accumulation. Character by character, step by step, blister by blister.

Cooper Hoffman carries the weight of the film as Garraty with a deft, unshowy magnetism. He never looks for sympathy; he simply walks with it, a hero with almost no heroism in him. David Jonsson’s McVries, a wry, complex mix of defiance and vulnerability, becomes the heart of the group, a moral centre amidst a wholly immoral act and there hasn’t been as compelling a duo on the road since Frodo and Sam set out from Bag End. Orbiting around these binary stars are a whirl of other bodies. Some we come to know quite well: Charlie Plummer’s Barkovitch providing queasy moments of friction within the group, Garrett Wareing’s Stebbins providing a quietly unnerving presence, staying aloof from the camaraderies and rivalries of the marchers; others we know only fleetingly. But every loss matters, each contestant loss hitting harder than the previous one.

It’s all overseen by The Major (Mark Hamill, commanding even in minimal screen time), an aviator sunglass-wearing personification of malevolent manifest destiny. The architect of The Long Walk, and someone who believes that suffering isn’t just beneficial, it’s essential – to weed out the weak and purify the American soul. The genius of the original story, and this adaptation, is that it doesn’t spend a lot of time trying to explain the mechanics of how the world got here. For them, and us, it doesn’t matter. The boys aren’t walking through backstory; they’re marching through consequence. The Long Walk isn’t interested in fomenting rebellion against its world; it’s interested in exploring the human cost of living in it. It trades in exertion, exhaustion and fleeting connection, moments of shared memory passed like contraband between the doomed. Its early miles are peppered with pitch-black moments of gallows humour, including addressing the scatological challenges presented by the need to walk at a constant three miles per hour come rain, shine or shit. The stumbles, the blisters, the muscle cramps all add to the drama, not just in who will fall next, but in how long the fragile, makeshift alliances can last before the inevitability of self-interest manifests.

The decision to shoot in sequence, reportedly averaging 15 miles per day, brings a dark verisimilitude to the parable on screen. Fatigue accumulates in the cast’s performances in real time; faces tighten, footsteps falter and dialogue stretch thinner with every mile. There’s no glamourisation of the landscape, no orchestral manipulations to swell the emotion, just the near silence of the weary scuff of dozens of aching footsteps. As part of King’s broader body of work, The Long Walk stands apart as one of his most ruthlessly non-supernatural explorations of banal evil. There are no monsters in the cornfield here. Just boys with sore feet, scared eyes, and nowhere to go but forward. Lawrence’s film adaptation honours that in a way that feels cinematically and commercially courageous.

As brilliant as it is, this isn’t a film that will likely encourage repeat viewings – making the march once will likely be enough for most audiences. If what matters most is the journey, not the destination, The Long Walk punishes both. It’s an experience in endurance, and our prize for walking with them one step, one breath, one blister at a time is that we don’t have to do it again. It’s an elegy with aching muscles; perambulation as polemic. And in its unrelenting tread, it dares to ask not how these boys will die, but whether they will live along the way.