I choose… Ben Richards. That boy’s one mean motherf***er.

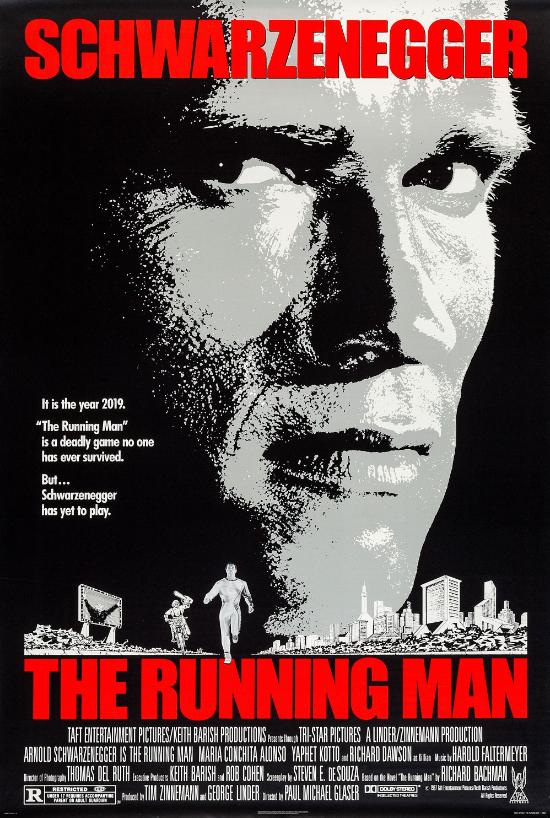

There’s a universe where The Running Man is the grim, furious dystopia Stephen King wrote under the alias of Richard Bachman back in 1982 (and soon, thanks to Edgar Wright, we might finally get to visit it). But the 1987 version lives in another reality entirely, one where Arnold Schwarzenegger in neon yellow spandex punches his way through game-show gladiators while one-liners fly thicker than bullets. Both versions claim the same title, but spiritually they couldn’t be further apart, and that’s half the fun. Arnie’s film doesn’t so much adapt King as forge his signature, open a Blockbuster account with it and head straight to the video nasties section.

Taken on its own terms, The Running Man is a riotous hybrid of dystopia and pro-wrestling pageantry, and it knows it. Set in a cheerfully fascist America of 2019, only a few years too early as it turns out and back when “the fascist future” still looked like a shopping mall with delusions of grandeur, the story pits Ben Richards (Schwarzenegger), a framed police helicopter pilot, against the nation’s favourite blood sport: a live-broadcast execution game where convicts must survive a gauntlet of gaudily-themed killers for the amusement of the masses. It’s Gladiators, if Gladiators had Pokémon’s concept team, Robot Wars’ props department, and Gosport’s own Richard Dawson smirking like the devil in a tuxedo.

Dawson, better known at the time as the real-life host of Family Feud, is the film’s secret weapon. His turn as Damon Killian, the oily ringmaster of the show, is so perfectly tuned that it pre-empts the entire next decade’s cynical exploitation of trash television spectacle and the rise of ‘reality TV’; his charisma makes the satire sting but his smarm makes it sing. Schwarzenegger, meanwhile, plays the whole thing with the blunt charm of a man who is oblivious to the satire and therefore ends up anchoring it with a lunkheaded authenticity. Every punchline lands like a hammer dropped by someone convinced it’s subtlety incarnate, which is exactly the kind of sincerity a movie this gaudy needs. Even Mick Fleetwood’s cameo seems like an in-joke taken to the next level.

Director Paul Michael Glaser (yes, Starsky himself) turns the dystopia into a visual disco of steel corridors and fluorescent violence, although his cinematic vision can best be described as workmanlike, if you’re feeling kind. The production design is part theme park, part scrapyard and perfectly mirrors the Reagan-era fantasy of television as both escape and punishment. Each “stalker” is a walking cultural metaphor, albeit rendered in latex and lunacy: Sub-Zero with his explosive hockey pucks, Buzzsaw with his weaponised power tools, and Dynamo, an opera-singing power-plant in sequins who looks like he lost a bet with Top of the Pops. It’s absurd, of course, but pointedly so; the kind of spectacle that makes you wonder how we ever ended up cheering for this sort of thing unironically.

The script, from Steven E de Souza, might have started out with the intent of skewering the media’s obsession with violence, but ended up having too much fun to linger on morality. But between the pyrotechnics and synth beats, the film manages a strange kind of prescience. Its vision of entertainment as a tool of mass distraction and of fake news sanitising state brutality certainly feels sharper now than it did then.

Watching The Running Man today, the gulf between King’s novel and Glaser’s film is almost academic. King’s version is furious and fatalistic; the movie is fluorescent and funhouse-violent, but both share a certain fascination with how systems consume people and how entertainment commodifies rebellion into ratings. Perhaps The Running Man’s finest achievement is that it’s a satire that accidentally becomes the thing it mocks, yet somehow still works. Its sugar-rush dystopia – equal parts sci-fi and showbiz – where every explosion feels like sweeps week is, as an adaptation, heresy. As a piece of 1980s action cinema, it’s ratings gold.