It’s always darkest before it gets even darker.

It takes a certain level of confidence to pivot from the elegiac drama of The Shawshank Redemption and The Green Mile to adapt The Mist, and a rarer kind of integrity to double down on despair when you’ve already delivered two of the finest redemptive dramas of the Stephen King cinematic canon. Frank Darabont’s third Stephen King adaptation doesn’t abandon his commitment to character or moral consequence, but it does invert the lens: faith curdles into fanaticism, courage calcifies into desperation, and instead of the hope of salvation, The Mist eventually clears to reveal something colder, crueller, and utterly devastating.

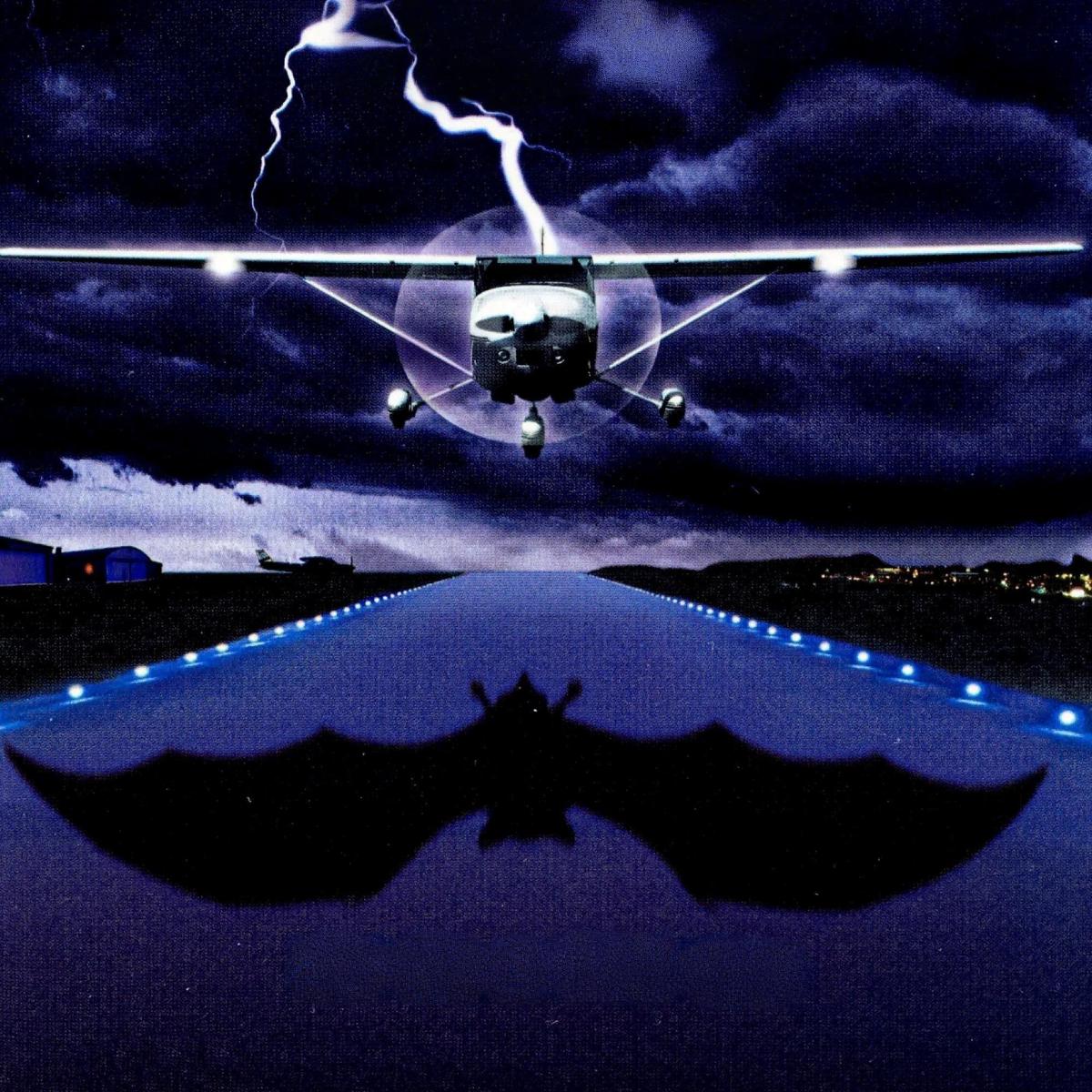

Based on King’s 1980 novella, The Mist centres on David Drayton (Thomas Jane), a commercial artist (in the film his works are the works of the late, great Drew Struzan) and devoted father who, along with his young son Billy (Nathan Gamble), becomes trapped in a supermarket with a group of townspeople after an unnatural fog descends across the town of Bridgton, Maine following an unseasonably ferocious thunderstorm the previous night. But the weather is the least of the shoppers’ concerns: there are things lurking in the mist – and in the hearts and minds of their fellow customers.

The source material was always one of King’s more pointed thought experiments: how quickly do social norms disintegrate under pressure? Darabont sharpens that edge, using the conventions of a disaster movie to collect its characters together to confront Lovecraftian horror rather than meteorological misfortune and turning the ensemble into a crucible of post-9/11 paranoia, groupthink, and ease with which frightened people can be manipulated into the most abhorrent acts.

The fluorescent-lit setting and handheld cinematography (courtesy of The Shield’s production crew, who Darabont hired to keep things raw and immediate) give the film an almost documentary urgency. Devoid of the mythic storytelling sweep of The Shawshank Redemption or The Green Mile, The Mist trades in B-movie tropes with A-list talent. The horror mechanics themselves are solid, and if the early 2000s CGI shows its age a little, that just adds to the feel of a hokey B-movie pushed to dark extremes and there’s a reason why many consider the black and white version of the movie as the definitive experience. As well as in the creature design, there’s a Lovecraftian sensibility in the lurking fear that the monsters aren’t just here, they may never stop coming. But as ever, in the finest traditions of horror, the real monsters are other people.

More frightening than tentacles, stingers and wings is Marcia Gay Harden’s Mrs Carmody, already a repellant figure in the novella here elevated to self-annointed prophet. Her descent from pious eccentric to egregious old testament cultist is played with a ferocity that could easily have tipped into cartoonish excess in less skilled hands and Darabont’s screenplay gives her the space to metastasise properly. She doesn’t hijack the survivors narrative; she reveals the vacuum at its centre.

That vacuum, of leadership, of reason, of hope, is what gives The Mist its power. The denizens of the supermarket’s emotional trajectories mirror their predicament: visibility declines, boundaries collapse, and everything familiar becomes suspect. Thomas Jane’s performance, all baffled decency and frayed nerves, grounds the film with someone the audience would hope to relate to. He’s no square-jawed hero figure, though, just a dad trying to keep his son safe and figure a way out of the nightmare. Around him are friends, acquaintances and even the occasional foe and Darabont populates the supermarket with a cast of character actors to die for. William Sadler, Andre Braugher, Toby Jones, Laurie Holden, Jeffrey DeMunn and Frances Sternhagen to name but a few bring an authentic sense of a community crumbling under pressure but there are no saints among them, only survivors – until there aren’t.

Darabont’s no stranger to maintaining fidelity to King’s broader themes while diverging from specific plot points to suit the transition to the big screen and here, despite the Old Ones-inspired spectacle, he keeps the focus firmly on the tension between personal morality and collective survival. The military experiment backstory is handled with just enough ambiguity to maintain plausibility without tipping into hokum, and the film resists the urge to moralise or editorialise the situation; it simply unfolds, unflinchingly watching a town tear itself apart in a crisis.

But even after everything he puts his characters – and us, the audience – through, Darabont saves his darkest and most savage deviation for last. His bleak, brutal last-minute rug-pull is delivered with such strategic audacity that even King himself hailed it as an improvement. It’s not merely the most twisted twist in the tale, a vicious reveal the likes of which M Night Shyamalan could only dream of, but a thematic culmination of Darabont’s conversation with King’s work and a dark inversion of Darabont’s own filmography to that point.

If The Shawshank Redemption is a hymn to hope and The Green Mile an elegy for grace, then The Mist is the requiem. Taken together, Darabont’s three Stephen King adaptations chart a descent: from belief, to doubt, to sacrifice. The Mist isn’t just Darabont’s bleakest film, it’s his most daring: a horror movie with the conviction to believe not only in monsters, but in the terrifying reality that there are some things you just can’t take back.