I’ve stayed in a few Travelodges like this.

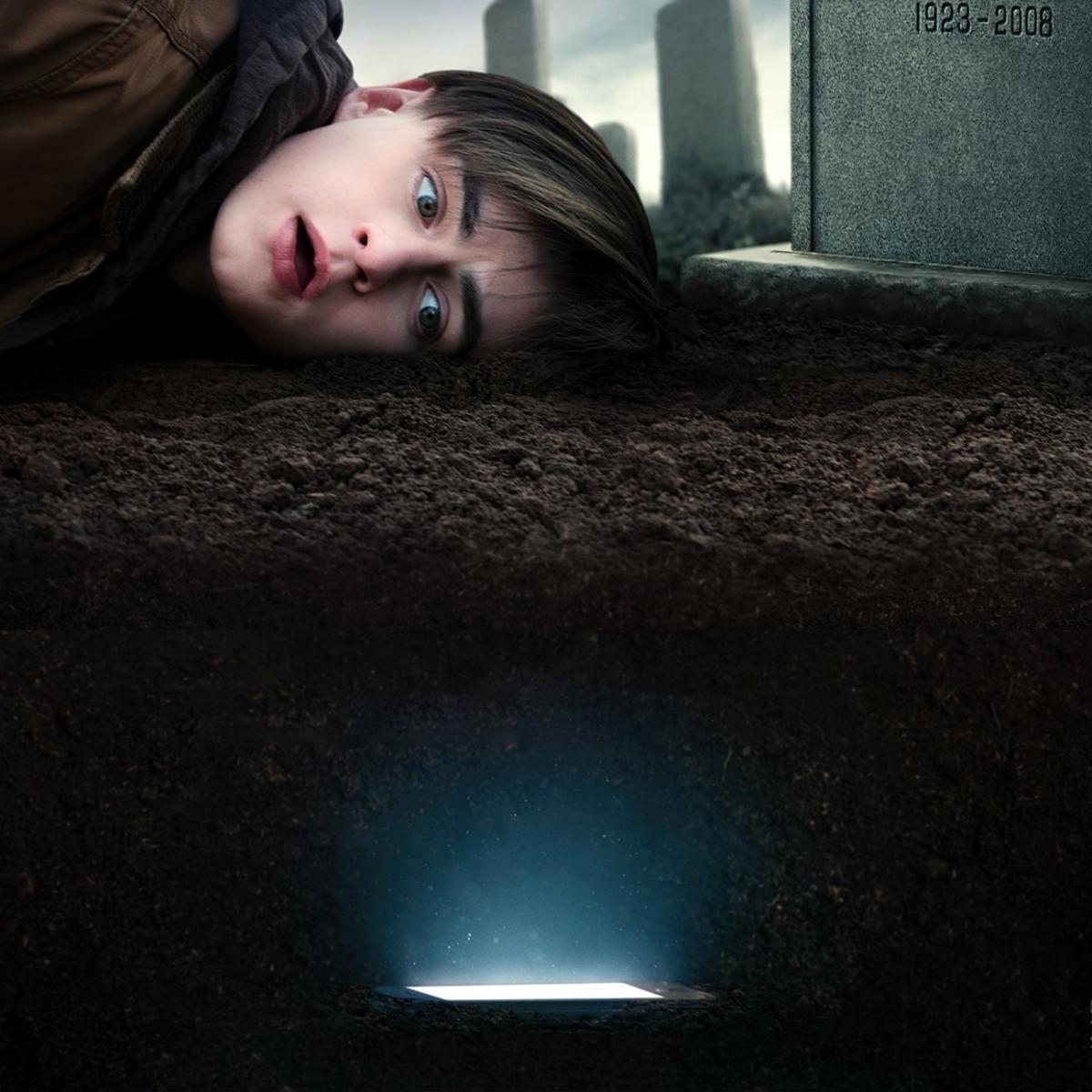

1408 locks its audience inside a single hotel room and spends nearly two hours proving that imagination can be the cruellest torturer of all. John Cusack’s Mike Enslin, a jaded writer who’s turned his scepticism into a cottage industry of debunking hauntings, checks into the titular room expecting boredom, not revelation. What follows isn’t a battle with ghosts so much as a slow, merciless dismantling of his disbelief, a séance conducted entirely between his mind and the room’s four walls.

Adapted from a Stephen King short story, 1408 understands the power of suggestion better than most horror films of its time. Director Mikael Håfström turns an anonymous hotel suite into a psychological crucible, layering dread through temperature, lighting, and the rhythms of repetition. The claustrophobia works in the film’s favour; making events theatrical without being stagey, and cinematic without relying on spectacle – a surprisingly elegant piece of filmmaking from a director often associated with mid-tier thrillers.

Cusack’s performance holds everything together. Alone for most of the runtime, he navigates the shifts from sardonic self-assurance to raw panic with unnerving authenticity, a one-man showcase that never feels indulgent. His exchanges with Samuel L Jackson’s hotel manager early on, a man who warns him with the calm fatalism of someone who’s lost this argument a hundred times, lights the story’s spark but once the door closes, it’s Cusack who fans the flames, embodying the kind of guilt-laden exhaustion that defines so many of King’s protagonists.

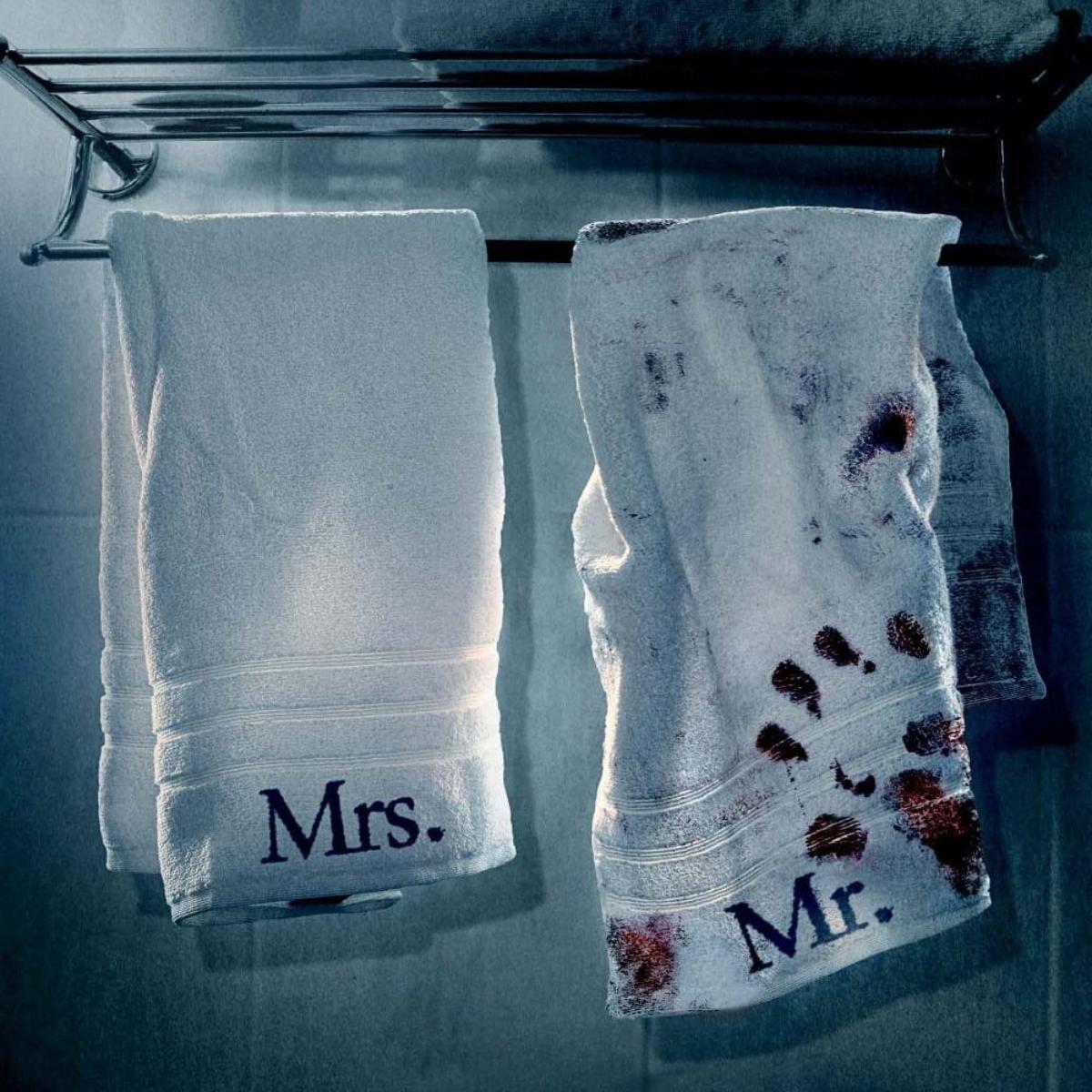

The screenplay by Matt Greenberg, Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski wisely chooses psychological torment over excess, reconstructing the text’s compact horror into something richer and more expansive. The film’s additions, particularly its exploration of Enslin’s grief over his daughter, deepen the emotional stakes and it’s one of those rare King adaptations that genuinely enhances the material by giving it room to breathe.

The horror in 1408 isn’t about supernatural logic but emotional collapse; the room manifests Enslin’s cynicism, grief and guilt, turning his inner monologue into interior decor and even when the imagery veers toward the literal – the dripping walls, the spectral phone calls, the ghastly apparitions – the tone never oversteps into parody.

Depending on which version you’ve seen, 1408 either allows Enslin to survive and confront proof of the supernatural, or condemns him to remain forever within the room’s purgatorial grip. Each plays differently but both fit: one offers redemption, the other damnation – twin conclusions that echo the story’s obsession with perception and truth, punishment and penance. 1408 is a compact story told with conviction, anchored by a lead performance that wrings empathy and fear from every seam of the wallpaper. It’s proof that you don’t need grand mythology or buckets of blood to unsettle, just a single room, a single mind, and the creeping suspicion that both are turning against you.