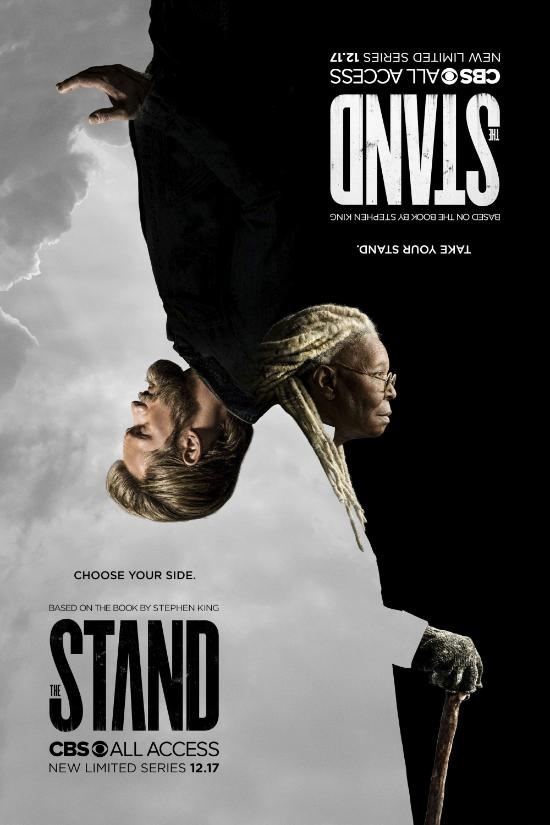

Imagine releasing a miniseries about a global pandemic during an actual global pandemic.

There’s a dark irony that the latest television adaptation of The Stand dropped right around the time the world found itself living through one, yet there’s something fitting about Stephen King’s great American plague parable being reinterpreted at the very moment the world went quiet. Where the 1994 adaptation captured the disillusioned paranoia of post–Cold War collapse, the 2020 version reflects the digital delirium of the information age, a story of contagion retold in an era when truth itself feels in terminal decline.

Boone’s adaptation keeps faith with King’s ambition but not his chronology, the story unfolding in non-linear fragments, beginning amid the aftermath of Captain Trips and working backwards through memory and confession, a storytelling approach that has become the lingua franca of prestige television in the late 2010s and through to the 2020s, the “present” punctuated by flashbacks that fill in the world before the fall. For The Stand, that structure proves both practical and poetic, allowing the show to condense the novel’s sprawling cast and geography into something comprehensible without sacrificing its sense of magnitude. It may trade King’s creeping dread for disorientation, yet there’s purpose in the disorder: it mirrors the way collective trauma is processed, not as a linear sequence but as chaotic flashes of ruin.

Where Mick Garris’ 1994 miniseries presented Randall Flagg as an Old Testament villain, a creature of fire and fear (and denim), Boone’s Stand understands that evil has, and always will, evolve. Alexander Skarsgård plays Flagg not as a cackling demon but as the ultimate populist, a grinning god of the algorithm. He doesn’t tempt; he provokes, ruling not through terror but through attention. His Las Vegas isn’t just a pit of sin but a kingdom founded on spectacle, fuelled by indoctrination, and built on propaganda. It’s a society that mirrors our own, where disinformation becomes de rigueur and the illusion of choice keeps everyone complicit.

That’s the most chilling stroke of Boone’s vision: Flagg no longer stands for chaos but for control disguised as freedom. In King’s novel, he feeds on fear; here, he feeds into echo chambers, his followers worshiping not evil but affirmation. It’s a portrait of how charismatic lies thrive in an age that mistakes confidence for truth, a reading that gets more prophetic by the day in an era of fake news, tribal politics and populist strongmen. The apocalypse, in this Stand, is epistemic: the collapse of a shared sense of reality itself.

Whoopi Goldberg’s Mother Abagail makes for a fascinating counterpoint. Where Skarsgård’s Flagg thrives on visibility, she exudes the quiet of faith unbroadcast, playing her not as a prophet of certainty but as someone wrestling with doubt, a believer aware that even righteousness can curdle into pride. Opposite her, James Marsden’s Stu Redman becomes the series’ moral ballast, weary but decent, a man holding on to humanity’s better instincts without needing to sermonise. Odessa Young’s Frannie, Greg Kinnear’s Glen Bateman, and Brad William Henke’s luminous Tom Cullen all bring deeper shades of humility and hope than their 1994 counterparts did, to a landscape stripped of both.

If Boone’s narrative compression occasionally pinches – nine episodes can’t contain all of King’s epic – it compensates through tone and rhythm. The series moves with a satisfying momentum, its nine hours passing in more kinetic and gripping fashion than the 1994 version’s ponderous six. It’s less an epic march than a fevered relay, the story constantly passing the baton between memory, myth and aftermath. That fluidity gives 2020’s The Stand a pulse that the earlier miniseries lacked, transforming King’s grand narrative of good and evil into something closer to moral archaeology, piecing together how the world fell apart and what fragments of decency remain.

The production itself, as you’d expect with twenty-five years of technical progress behind it, feels more sumptuous than its predecessor. Its desolate highways and empty cities, shot with sterile beauty feel completely authentic, widening the shots that Garris was forced to keep tight to avoid revealing how contrived his apocalypse was. Boone’s pacing carries the weight of aftermath rather than event and it’s a masterstroke that James Gunn would be proud of for each episode to end with a pithily apt needle drop.

Its greatest addition comes in the closing chapter, a new coda written by King himself. This addition, set beyond the novel’s end, reframes survival not as divine vindication but as continuity: flawed, uncertain, yet defiantly human. It’s as if King revisited his own myth and found compassion where once there was punishment. For all its inevitable compromise (The Stand may defy a fully satisfying adaptation), 2020’s attempt emerges as a thematically modern iteration of King’s apocalyptic saga, understanding that the real battle between good and evil isn’t fought in deserts or dreams but in the fragile space between truth and lies. The 1994 version had faith that good would ultimately triumph; Boone’s believes that triumph is fleeting and that survival is a temporary reprieve before evil regroups, reorganises and returns to try again.