Stephen King finds the fear in fan fiction.

When Misery was released in 1990, it marked the second time Rob Reiner had translated Stephen King’s most introspective writing to the screen. But where Stand By Me captured the author’s sense of lost innocence; Misery explores his fear of creative captivity. While Mike Flanagan would later show an intuitive understanding of King’s flair for terror and while Mick Garris’ workmanlike fidelity guaranteed him multiple collaborations, there isn’t perhaps another director who so completely understands King with all the ghosts stripped away, finding terror not in the otherworldly, but in the everyday horrors of dependency and control.

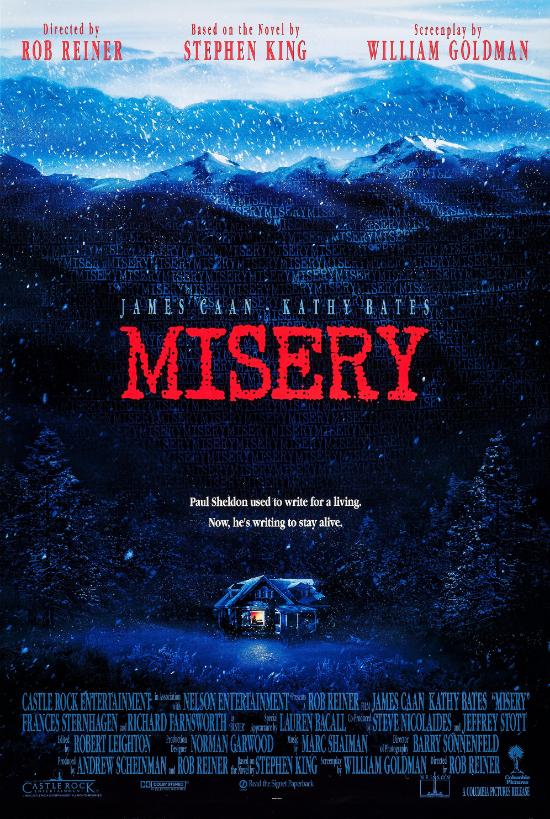

King’s novel always read like an autopsy of fandom: a writer dissecting his own anxieties about success, the burden of expectation, and the violence of being adored in the wrong way, for the wrong reasons. Reiner’s film doesn’t flinch from that, but he hones it into something even sharper, a duel between authorship and fan fiction. James Caan’s Paul Sheldon is every writer’s self-portrait (and King has penned more than a few) in their pomp: capable, complacent, smugly certain of control. Kathy Bates, as his self-appointed nurse and number one fan Annie Wilkes, weaponizes devotion into mania with such terrifying charm and precision that she annihilates the border between admiration and obsession.

Having already trusted to capturing King’s tenderness and loss in Stand By Me through selective fidelity and an understanding of the heart of the story, he approaches Misery with the same instinct for honesty, even as the subject matter darkens. The novel unfolds unfilmably inside Paul Sheldon’s drugged and desperate thoughts, but Reiner knows cinema can’t replicate that interiority directly and wisely chooses clarity over viscerality. There’s no sensationalising Paul’s experience, or taking them to a metaphysical place. Reiner pares everything back to reality; no hallucinations, no dream sequences, no gothic excess. He lets the claustrophobia and confinement do the work, squeezing every drop of dread from pain, silence, and the terrifying calm of Annie’s care. It’s a triumph of discipline: horror built from empathy, not extremes.

It helps that Caan gives one of his most intricate performances. He plays Sheldon as a man learning humility by inches, his physical helplessness obligating emotional candour but it’s Bates who dominates the film’s malicious core. Her Annie is no caricature of madness; she’s lucid, lonely, and terrifyingly logical. Even her volcanic outbursts are moments of righteous clarity within her own deranged world view. Bates earns her Oscar with every single line, giving us a villain who sees herself as the hero of her idealised epic romance, nursing her wounded knight back to health and back onto the path of artistic purity.

King knows, deep down, that given the chance fans will always kill the thing they love – and he concentrated that self-destructive obsession into the character of Annie Wilkes. Every page Sheldon types under duress becomes a negotiation between art and audience, a twisted parody of the feedback loop every creative artist endures. Annie’s insistence that he “bring Misery back” is easily read as the cry of every fan resisting artistic growth, demanding the comfort of repetition. Three decades on, Misery hasn’t aged into nostalgia; it’s oxidised into relevance. At the time, King’s novel and Reiner’s film were chilling in their plausibility. In hindsight, it now looks chillingly prescient, foreshadowing the current era of parasocial attachment and weaponised toxic fandom. You just know Annie would have been a proud member of The Snyder Cult.