Wild Things will make more than your heart sing.

Trashy, tawdry, and scandalously self-aware, Wild Things lures you in with the promise of swampy Floridian sleaze, but it doesn’t just seduce you – it lifts your wallet and your watch while you’re distracted. Marketed as an erotic thriller with a capital E, what it turns out to be is a far darker, cleverer neo-noir that’s merely masquerading as softcore titillation. Much like the film’s plot itself, Wild Things hides layers of deception beneath its glossy surface.

The late 1990s was a time when the erotic thriller still had mainstream cinema in its sleazy clutches. The success of Basic Instinct in 1992 sparked a wave of copycats, all angling for a share of the same illicit appeal. By 1998, though, the genre was gasping its last steamy breaths thanks to too much heat and not enough substance. Wild Things arrived just in time to serve as the genre’s final hurrah, but with a delicious twist. What initially seemed like maybe the most gratuitous of the bunch was actually a subversive celebration and critique of the genre all at once, wrapped in layers of betrayal, blackmail, and murder. It was a Trojan horse, offering sweaty salaciousness on the outside but delivering a sharply written, darkly comedic thriller that’s as cold-blooded as the gators lurking in its Everglades setting.

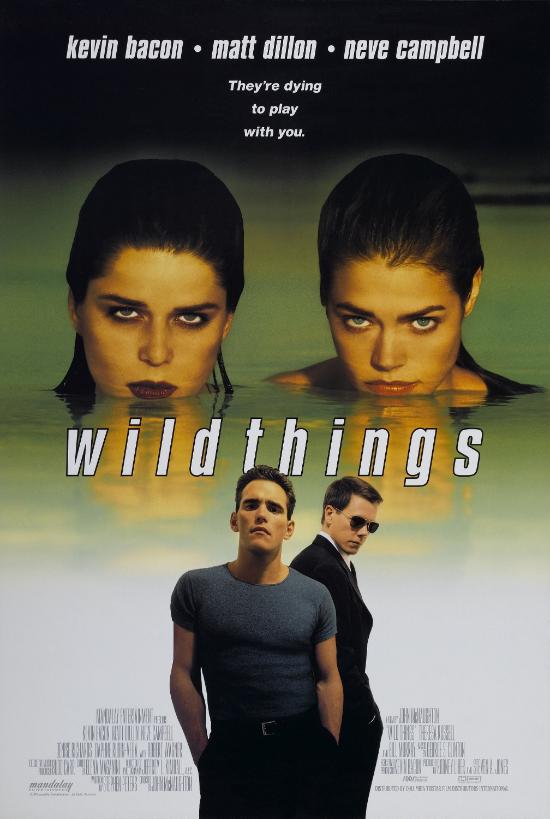

Director John McNaughton (Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer) clearly knew what he was doing. The film’s borderline lurid marketing leaned into its more exploitative elements—salacious posters, steamy trailers, and the promise of ménage à trois pool scenes were deployed to maximum effect. But beneath the sweat and scandal lies a twisted tale of greed and double-crosses that would make even the most cynical noir enthusiast smile.

The cast is as starry as it is surprising. Sure, there’s Matt Dillon playing his sleazeball guidance counsellor with exactly the right level of self-aware smarm, Neve Campbell stepping boldly away from her Party Of Five roots to follow Scream with this, delivering a simmering performance as Suzie, while Denise Richards blends vapid entitlement with deadly cunning in a role that would make any femme fatale proud. Kevin Bacon, meanwhile, brings his trademark intensity to the mix, playing a detective whose motives seem straightforward until they aren’t, adding yet another layer of deception to the film’s tangled web.

But then, out of nowhere, the film plays a couple of wild cards. Robert Wagner saunters into the film exuding his trademark charm at first, only to take a left turn into steely ruthlessness that may start to explain how Jonathan Hart really made his fortune but it’s Bill Murray’s turn as an offbeat, sleazy-yet-competent lawyer, bringing his particular brand of laconic wit and mischief to what might be the film’s biggest con. His presence feels almost surreal, but somehow, it works perfectly in a story this gloriously deranged.

To call the plot twisty would be a profound understatement. Wild Things doesn’t just twist; it contorts, backflips, and ties itself into increasingly ludicrous knots. It’s the kind of film that delights in wrong-footing its audience every few minutes, revealing a new double-cross or unexpected connection until you’re left wondering who – if anyone – you can trust. Just when you think it’s finally over, there’s another scene. And another. Even the end credits become a dizzying cascade of bonus reveals, each one adding to the film’s darkly comic tone. The metatextual glee is palpable – Wild Things knows you think you’ve outsmarted it, and it’s already two steps ahead.

In hindsight, it’s almost miraculous that a film this strange, sleazy, and smart even got made at all. The late ’90s studio system was still indulging in riskier fare, but it’s hard to imagine today’s more sanitised cinematic landscape giving a project like Wild Things the green light. Perhaps that’s why it feels so singular – a neon-lit fever dream of sweaty betrayals and improbable alliances that both revels in and critiques the trashy genre it seems to embody.

Looking back, Wild Things deserves to be remembered not as an anomaly or a guilty pleasure, but as a neo-noir gem that knowingly danced along the edge of bad taste. It’s not just a movie; it’s a con – a long con, in fact. It played us all with its sultry sheen, but beneath that slick surface lay one of the cleverest films of its time.