Don’t be obtuse – read my acutely observed review of The Shawshank Redemption.

Within the oft-mentioned but rarely seen stone walls of Stephen King’s Shawshank Prison, Frank Darabont’s adaptation of Rita Hayworth and The Shawshank Redemption finds light in a subtle illumination of faith and philosophy that pierces despair, turning confinement into transcendence and a prison drama into a meditation on grace, guilt, and the possibility of redemption,

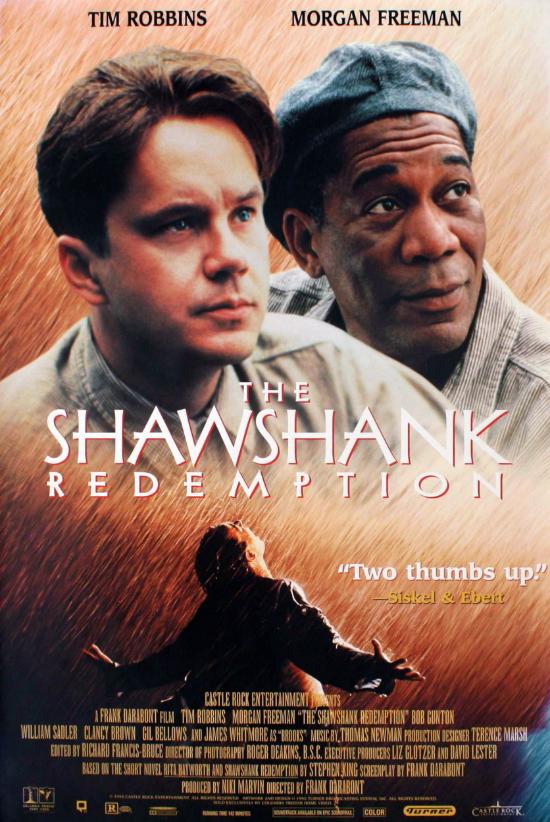

Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins), convicted of a crime he didn’t commit and condemned to Shawshank by his unwillingness to show any emotion arrives at the prison in something of a daze, catching the eye of Morgan Freeman’s Red, a man long resigned to the rhythms of incarceration. Freeman, whose narration transcends to testimony, brings a warmth to the cold institutional surroundings, creating the conditions under which a friendship that will come to define the movie could possibly develop.

Darabont reshapes King’s compact confessional sting in the tale into something approaching mythology, or even scripture. Time here is both the warden and the warden’s undoing, each day a step of penance or defiance. The intricacies of the story, its interlocking events and innocuous incidents with profound consequences, isn’t just preserved in the transition to the screen but almost beatified. Each humiliation, each fleeting kindness, lands with the weight of parable, building a gospel according to Red. The violence in The Shawshank Redemption isn’t about blood, but about the erasure of dignity. Darabont’s genius lies in how he frames that stripping away of humanity against the flicker of an inner light: Andy’s integrity as both shield and sword. In a place where men are robbed of everything, his refusal to let the circumstances define his destiny has a power all of its own.

But every saviour needs his antithesis and The Shawshank Redemption‘s arrives in the form of Bob Gunton’s marvellously odious Warden Norton. Norton embodies the all-too-familiar hypocrisy of American evangelical Christianity: pious in posture, mendacious in practice. He quotes scripture with the smug assurance of the saved, twisting words meant for compassion into instruments of control. Shawshank is his kingdom and he is the power and the glory – or so he continues to believe until his hubris brings his undoing. Around him orbit men who’ve traded conscience for creature comforts; guards, businessmen, bureaucrats form a legion of corrupt figures, exploiting the prison and its inmates far beyond the call of justice.

Robbins plays Andy as a man already half-removed from the world’s gravity, and contemplating cutting ties altogether. His quiet intellect shaping him into something almost prophetic just as surely as he shapes his sandstone chess pieces. Red’s narration, never overbearing and used with precision to cover only what necessary to tell rather than show, observes how his calm bends reality: how his fearlessness causes fear to recede around him, and how he knows how to wield even the smallest gestures to maximum impact. He builds, moment by moment, not a rebellion but a movement of rehumanisation of the dehumanised. Not with threats or violence but calm, implacable logic and a cunning grasp of the politics of the quid pro quo. When Andy and his crew resurface the prison roof under the blazing sun, drinking cold beer like apostles at a second-hand Last Supper, the moment feels blessed, but by human grace rather than divinity.

Roger Deakins’ cinematography makes confinement look inescapable yet fragile. His light, filtering through dust and smoke, turns Shawshank into a chapel built from concrete and despair while Thomas Newman’s score soars above it like benediction. The moment Andy plays The Marriage of Figaro over the loudspeakers isn’t just a simple act of rebellion; it’s a powerful reminder that art and music can set us free, and that nobody should be denied their benefits. The camera lingers on men halted mid-step, their faces turned upwards as if sensing something larger and better than their current circumstances isn’t as out of reach as they were led to believe.

Every technical choice reinforces this sense of social transmutation. Terence Marsh’s production design gives the prison a monastic weight; the repetition of stone, steel, and shadow shaping both confinement and contemplation. Richard Francis-Bruce’s editing moves with liturgical rhythm: measured, reverent, unhurried and Darabont resists easy catharsis, letting situations linger and unfold in their own good time until we reach the final act of release and retribution. Andy’s escape, crawling through filth into cleansing rain, fulfils every symbol the film has planted: baptism, resurrection, deliverance. When the storm breaks and Andy stands, arms outstretched, Darabont allows the image its full biblical weight without irony. That irony is saved for the fiendish trap that Dufresne has set – in plain sight of us all – that ensures that Norton and his corrupt cadre of guards are taken from on high and will find their place behind their own bars.

Zihuatanejo, the Pacific dream that haunts Dufresne and Red’s final conversations, becomes whatever version of paradise the viewer requires. A literal escape to paradise, it can be read as an analogue for heaven, or Nietzsche’s slate of sin wiped clean. Robbins himself called it the promise of a place beyond all prisons; a horizon we imagine when endurance is all we have left. Andy’s final act is one of his most transcendent and rebellious in today’s age of cynicism and selfishness: having achieved his longed-for paradise of complete freedom, he makes sure that Red can get there too, saving him from the same fate that took old Brooks.

King’s original story was a masterpiece of plotting but Darabont’s adaptation expands and elevates it in every conceivable way. Every single cast member is brilliant, and the film’s meandering path through Dufresne’s prison years is mesmerising as it charts the twists, turns, tragedies and triumphs of a game of chess played over decades. The moments of kindness and humanity shine out against the bleak backdrop of a corrupt and brutal system but at its very soul, The Shawshank Redemption is a love story: a Platonic elegy to brotherly love.